A Little Synthi

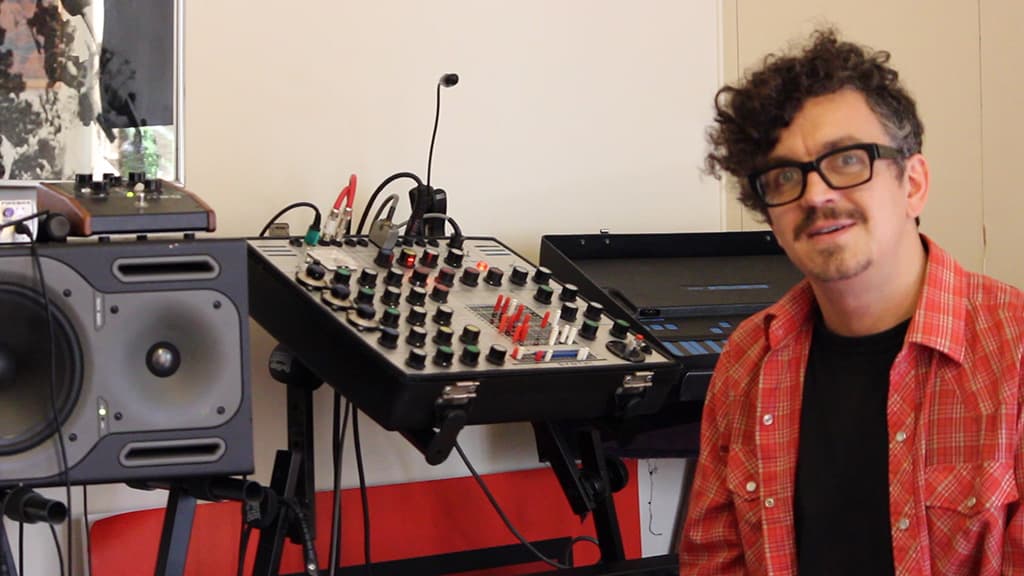

Mathew Watson’s classic EMS Synthi AKS synthesiser unearths a whole generation of Dalek nightmares and Other Places.

Story & Photos: Jason Allen

If you’ve heard Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon, you’ve heard an EMS Synthi AKS. It was used by David Gilmour and producer Alan Parsons to create the classic synth track On The Run. And if you’ve had nightmares about Doctor Who’s Daleks, they’ve probably been soundtracked by an EMS synth.

The London company’s synths powered the BBC Radiophonic Workshop into the ’70s; Brian Eno, Yes and David Bowie were all EMS fans; and the company led the world in the production of affordable synthesisers for gigging musicians. EMS was the UK’s answer to Moog.

Following on from the successes of EMS’s original design — the affordable VCS3 synth — and the portable Synthi A version, EMS released the Synthi AKS. Positioned as an expanded version of the Synthi A, the AKS included a membrane keyboard and sequencer mounted in the lid of its Spartanite case, hence the ‘KS’.

In 1972, at a time when a modular synth could be the size and price of a small house, the Synthi AKS sold for around £450 — the equivalent of around £5000 today.

Compared to the processing power available now, the AKS was a relatively simple beast — three oscillators, noise generator, ring modulator, low-pass filter and a spring reverb. It has two control voltage sources, including an envelope generator, accessed through a joystick and a trigger button respectively. Two mic inputs and two line inputs allowed you to use the Synthi as a powerful sound processor, and, due to the difficulty musicians not versed in synthesis had using EMS products as melodic sources, a lot of units ended up not doing much more than that.

THE AKS PALETTE

One of these legendary synths has found its way to Melbourne’s Mathew Watson, who is about to release his second AKS-based album as Other Places. Mathew’s Synthi AKS has an impressive lineage — it has passed through the hands of famous TB-303 circuit bender Robin Whittle to Mathew’s mentor, electronic music pioneer Ollie Olsen. Mathew was first captivated by the possibilities of the AKS when Ollie temporarily expanded his duo Fading Fires. For a time, the live ensemble became a trio with Ollie building rich soundscapes via his AKS and a loop pedal around Chris Rainier’s treated lap steel, and Mathew on drums and Roland SH-09.

That AKS now has pride of place at Mathew’s studio. “I never asked to buy it, not once. I always saw it as a part of Ollie,” explained Mathew. “A mutual friend mentioned to Ollie that I was really inspired by and in awe of it. Ollie then offered it to me (for a price!) with the instruction that I should never sell it. I feel the synth will always truly belong to Ollie but I am the caretaker.” Its abstract, physical nature took Mathew a lot of experimentation to come to terms with, but this has led to an almost poetic understanding of its character. “When people who aren’t familiar with it look at the AKS, they think it looks like a game of Battleship. It may look complex, but it’s actually quite simple when broken down. Creating sounds with the AKS is similar to mixing paint on an artist’s palette — from the selection of six or so carefully chosen paints the artist knows they can make thousands of colours. The AKS is so raw and brutal. It’s stepping back in time to before electronics were refined. The sounds it makes are just so exciting.”

MELODY MODULE

The history of EMS synths shows a general skewing towards out-there cosmic soundscapes. Probably because of the brand’s close ties to The BBC Radiophonic Workshop (EMS co-founder Peter Zinovieff played in Unit Delta Plus with Workshop alumni Brian Hodgson and Delia Darbyshire), which used re-rigged test oscillators and the Wobbulator for sound generation before EMS came along. And many of the German Kosmische and Krautrock artists of the ’70s — including Faust and Klaus Schulze — embraced the chaos of the VCS3, Synthi A and Synthi AKS to execute their psychedelic visions. Composer Tristram Cary’s (also an EMS co-founder) sci-fi soundtracks like Hammer’s 1967 Quatermass and The Pit featured EMS synths, as well as a long run of Doctor Who credits — including those devilish Daleks.

Mathew was smitten by “the mystical, otherworldy nature of what their music was about and in turn, the instruments they made that music on”. But when he added an EMS DK-1 monophonic keyboard controller, the EMS world of sound opened up far beyond those cosmic expositions… into melody. The DK-1 was originally released in 1969 as an interface for the VCS3, and gives the player 37 keys, an extra oscillator and two control voltage outputs. “Other Places started the moment I got the DK-1,” said Mathew. “The AKS is not generally used as a monosynth. The more I was told it was purely for sound effects and processing, the more determined I became to extract melodic behaviour from it.” Mathew doggedly pursued his contrarian line, learning to make the AKS produce soaring leads and dirty bass sounds. “The quality of its sound is so unique, but as soon as I had a means of playing melodic music, it opened everything right up.”

If you’ve had nightmares about Doctor Who’s Daleks, they’ve probably been soundtracked by an EMS synth

COSMIC CUT ’N’ PASTE

Inspired by, but not limited to the technology of the ’70s, Mathew procured a laptop and a copy of Ableton Live and got to work. “The first album eventuated out of six months of trial and error. I’d play a line in from the AKS, which would then inspire a drum pattern or rhythm. Sometimes I’d start by setting up something simple in Ableton using a Drum Rack with a Roland TR-808 or 606 emulation and then come up with a textural or melodic idea.” Mathew laid down idea after idea, filling his hard drive with drones, leads, basses and grooves. The narrative of the album began to take shape. “I liked the idea of something futuristic and cosmic. I wanted it to sound like the BBC Radiophonic Workshop with Keith Moon playing drums,” Mathew explained. Luckily for his inner-city Melbourne neighbours, Mathew retired to his hometown of Stawell in western Victoria to work on his drum parts: “My uncle offered me his garage. I’d take all my drums and mics and my laptop and just experiment with different drum ideas.” The drums for the album were then tracked with engineer Nick Treweek (Augie March, Glen Richards) at his Fairfield studio.

Mastered by Byron Scullin at Deluxe Mastering, the self-titled Other Places dropped in November 2011. It garnered strong support from Australian independent radio, a feature interview on Germany’s national broadcaster Deutsch Welle and landed Mathew a support slot for New York math-rockers Battles. The critical acclaim didn’t hurt Mathew’s career as a drummer, either. As the album hit the airwaves, Mathew was helping lead 110 other drummers in the 111BoaDrum astronomical happening conducted by Japanese experimental legends Boredoms in Byron Bay. In 2012, Mathew performed as part of Yeah Yeah Yeah’s guitarist Nick Zinner’s 41 Strings/IIII project at Sydney Opera House for the Sydney Festival, a piece inspired by Earth Day and Vivaldi’s Four Seasons.

Mathew Watson runs AudioTechnology through the EMS Synthi AKS and what it can do.

TAKE TWO

Mathew has now gone back into the studio and is completing his second Other Places album. From the album’s inception, Mathew has thoughtfully tackled one of the central questions facing all musicians now working with synthesisers and computers — what is the best and most productive way to create music when you are faced with infinite possibilities? And Mathew is conscientiously applying the lessons learnt from album one.

“The thing I took away from the first album was that I wanted to develop my process,” continues Mathew. “How do I set up my studio so I can sit down, turn everything on and make music?”

A time-honoured strategy composers have found for the problem of too much freedom is to self-impose limitations. Stravinsky summed up the problem nicely in Poetics of Music: “I experience a sort of terror when, at the moment of setting to work and finding myself before the infinitude of possibilities that present themselves, I have the feeling that everything is permissible to me… My freedom thus consists in my moving about within the narrow frame that I have assigned myself for each one of my undertakings.”

Mathew’s ‘narrow frame’ is a setup with the AKS at the core, Ableton as drum synth and recording medium, a Line 6 loop pedal to facilitate a live performance-based workflow and a Dave Smith Instruments Poly Evolver synth for extra processing and textures. The key is having everything patched to everything else — modular, flexible and ready to perform at a moment’s notice. “I now have a constant setup,” said Mathew. “I always have everything connected. If I’m getting stuck creatively I can just feed a signal into the looper, or send a line out of Ableton into the AKS. If I feed a drum machine from Ableton into the AKS and patch it though a filter while I’m also playing a melodic line, it just explodes. I wanted to get more into an organic way of creating electronic music. I’m responding to what I’m hearing, not a static mix.”

By holding himself to this discipline, the act of writing becomes easier, but most importantly each session nets useful music. “You can noodle for years on end, have a hard drive filled with sounds, and build music by layering those sounds, but the music you make like that sounds a certain way — it’s cut and paste,” said Mathew. “I’ve found that the best creative moments are born out of mistakes and fleeting moments of weirdness.”

www.otherplaces.co

www.soundcloud.com/other-places

www.otherplaces.bandcamp.com

RESPONSES