Audiophile Recording: Heavenly Voices

This story began with an email from Marshall Cullen of Foghorn Records. He’d been listening to an SACD Audiophile release of an album called ‘Heavenly Voices’ by pianist Fiona Joy Hawkins and violinist/soprano Rebecca Daniel, and commented that the piano sound “blew me away”. We tracked down producer/engineer Cookie Marenco to find out how she did it…

When introduced to Cookie Marenco, Brian Eno said, “‘I shall not forget that name.” It’s certainly a memorable name, and one that’s been popping up on the fringes of the audio industry for decades – typically associated with high quality sound, leading edge recording technologies, audiophile recording labels and high fidelity audio streaming services. In that respect she’s an audio version of those Silicon Valley mavericks who spend their lives exploring the edges of new technologies in search of a better user experience.

Marenco started playing the piano at age four, and was teaching piano by age 14. She was invited to join the San Jose Symphony as an oboist at age 18, but decided “I don’t want to play Beethoven for the rest of my life”. She went on to study North Indian Classical Music and sitar with Krishna Bhatt, a connection that led her to working with Zakir Hussain and numerous others who “took me into a totally different world”.

Despite being a renowned recording engineer with numerous awards and Grammy nominations, Marenco is quick to point out that she never intended to be a recording engineer. She was playing in experimental jazz/improvisation bands when a musician friend convinced her that her house was the perfect place for a studio. Urged on by Mark Isham and others who appealed to her interest in film composing, she decided to “buy a bunch of gear, set it up, and learn how to use it.” OTR Studios (originally ‘Out There Recording Studios’) officially opened on New Years Day in January 1982, and is now the oldest owner-founded studio still operating in the San Francisco Bay Area. It’s also home to Marenco’s ‘Blue Coast Records’ label that specialises in high quality audiophile recording in the DSD format, and is where the album Heavenly Voices was recorded, mixed and mastered.

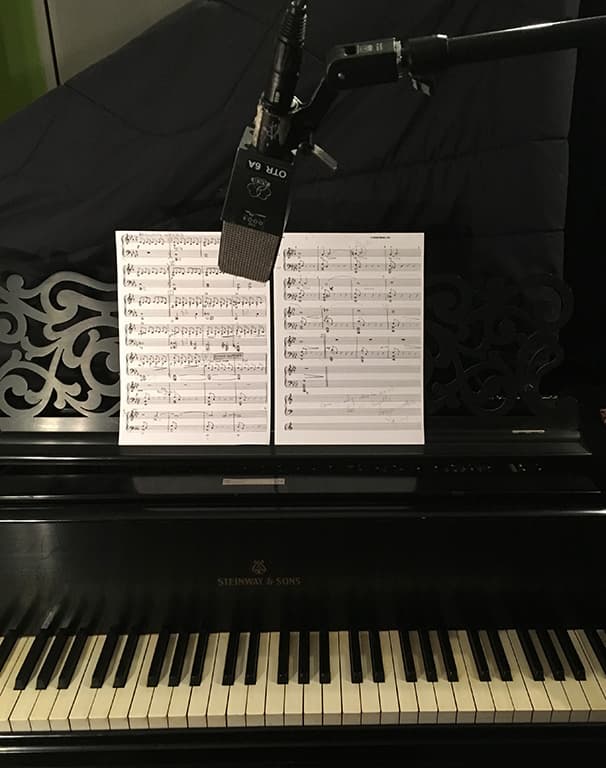

Greg Simmons finds Cookie in the studio polishing the very piano that motivated this interview. After exchanging formalities, they got down to business…

COOKIE’S PIANO

GS: Tell me about that beautiful piano of yours…

CM: Sure. It’s an 1885 Steinway B, a seven foot grand. It’s from my days of being a piano player and teacher. It’s only got 85 keys…

GS: 85 keys? Do you mean to say that three keys are not working?

CM: The three keys at the far right-hand side on most grand pianos… they don’t even exist on this one! In 1885 they didn’t see a need to put in those keys. The reason why they added them in later years was because there’s something like 10,000 pounds of pressure required on those high strings in order to get them into tune. I used to be a piano technician before I was an engineer, and, as I understand it, those additional three strings at the top – B-flat, B and C – are really just there to take the tension off the notes immediately below them, so that those notes sound better…

GS: How did you end up with an 85 key piano?

CM: Well, it wasn’t my intention… Having decided to pull the trigger and buy a Steinway, I went to Sheldon Smith – a gifted Steinway specialist – and said, “I want a piano that Art Lande or Arthur Rubinstein would sit down to play with no questions asked.” Eventually he found one, but he wouldn’t let me see it. I had to wait a year for it to be rebuilt, and when I finally saw it I was a bit freaked out because those last three keys weren’t there. Also, it’s got this incredible filigree and etchings on the legs, a very ornate music board, and so on. It just seemed so over-the-top! It was nothing like the piano I imagined seeing in my room.

GS: No wonder he didn’t want you to see it earlier…

CM: Yeah. I was still studying classical at the time and asked my teachers, Jeanne Stark and Art Lande, “What do you think?” They both asked in return, “Does it sound good?” I said, “It sounds fantastic!”, and they said, “Then don’t worry about those missing three keys…” The sound was the bottom line, of course, so I bought it and quickly grew to love it. It sounded amazing after it acclimatised to my room, and it still does.

It wasn’t originally black, either. Sheldon had put over a dozen coats of black lacquer on it and he was very proud of the finish. I got that piano before I started the studio, and in those days I never let anyone touch the case. No fingerprints! Then I opened the studio for business and somehow those darn drummers managed to run their cases into it; chipped the paint, scratches and fingerprints, you name it. I’m still the only one allowed to dust it, and I always do it ‘with the grain’! [laughs]

GS: Oh, this is very interesting – a great piano with an equally great story behind it, and it dates back to 1885! By that time Steinway had factories in Hamburg and New York, but there are subtle differences in tonal character between a Hamburg Steinway and a New York Steinway. The sound you’ve captured on this album seems to have elements of both; the harmonic complexity of the New York models but with the more controlled harmonic detail of the Hamburg models. Do you know where yours was made?

CM: That’s a good question! If I remember correctly, Sheldon said this piano had been in Japan and then in Seattle, and I think he mentioned that he got the ornate music board from a different piano. It doesn’t say ‘Hamburg’ or ‘New York’ on the frame, but Mr. Steinway signed it and people come from all around the world to record on it…

GS: Then it’s a treasure regardless! Are those missing high notes ever a problem?

CM: Well… Until 1925 they didn’t have those notes on the piano anyway, so there’s not much music that uses them. Fiona writes music that uses those three upper notes, but on my piano she manages without them.

PIANO MIKING

GS: Speaking of Fiona’s music and your piano, can we talk about how you miked your piano for Heavenly Voices? I’ve listened to the album many times – in DSD through a CEntrance DACport HD into a pair of Neumann NDH20 headphones, and also through my Grover Notting CR1 cross-reference monitors for the imaging and all those other things that are hard to judge in headphones. Apart from the overall lovely sound, one thing that really struck me was the imaging on the piano. It’s a very wide image with the lowest notes on the far left, the highest notes on the far right, and the rest of the notes transitioning smoothly between them. It’s as if I’m sitting on the piano bench…

CM: Player’s perspective, of course!

GS: Of course! It reminded me of some piano recordings I listen to regularly on my Thinking Music playlist. They’re albums by George Winston, released on the Windham Hill label many years ago. I know that you worked for Windham Hill many years ago, so I’m just wondering… Is there any connection between those George Winston piano recordings and your piano recordings?

CM: You’re referring to the George Winston albums that were recorded by Steven Miller, right?

GS: Yes, those ones…

CM: I’m glad you brought that up because there is a connection there. I’m a pianist and I used to work as a piano tuner, so I’m particularly sensitive about how the piano should be recorded and how it should sound. I spent the first 10 years of my audio engineering life experimenting with piano miking, trying to find something I was happy with. Then, one day, Steven [Miller] came to visit my studio. He took one listen to my piano and asked, “Do you have a pair of 451s?”

GS: AKG C451s? With the CK1 cardioid capsules?

CM: Yeah! Back then I was reading all the books about sound recording and they were saying things like “Put two 414s over the hammers and do this and do that…” I always hated that sound. I wanted the sound ECM got on their piano recordings of Art Lande, Chick Corea and Keith Jarrett. Steven’s recordings of George Winston were much closer to what I wanted to hear.

GS: We must’ve been reading the same books! [laughs] What did Steven do with the 451s?

CM: Well, I gotta tell you, where he put those 451s… I was shocked by how good they sounded. It changed my whole concept about miking the piano…

GS: So the piano sound on Heavenly Voices was captured with a pair of 451s?

CM: Oh no, I didn’t continue using the 451s. I switched over to a pair of B&K 4012s…

GS: The high voltage version of the 4011 cardioid?

CM: Yeah. The piano’s SPL is so intense with that kind of mic placement that, to my ears at least, the 4011s couldn’t handle the pressure on the top end without a slight bit of distortion. But the 4012s were fine…

GS: That’s interesting, and it also makes sense. The 4012 operates from +130 Volts, rather than the standard +48 Volts provided by phantom power, which gives it a considerably higher SPL capability. I was using the omni version of those B&K high voltage mics for some time and they could handle anything!

CM: Right… So I basically took Steven’s mic technique for making those George Winston albums, changed mics from the 451s to the 4012s, and never changed again…

It changed my whole concept about miking the piano…

GS: [smiling and nodding optimistically]

CM: What are you doing?

GS: Holding the sustain pedal…

CM: [laughs] Are you waiting for more information?

GS: Yes please! We haven’t talked about the actual microphone placement yet.

CM: Well, mic placement is a little bit like a Ouija board sometimes…

GS: A Ouija board? That’s a good analogy for mic placement! I find it amusing how people will read about someone’s microphone technique and faithfully mimic it, right down to the millimeter and degree, in the hope of getting the same sound – oblivious to the reality that you’ll intuitively change that placement by centimetres and degrees from one recording to another to best serve the music, even when you’re recording the same piano in the same room with the same mics and the same performer.

CM: Exactly…

GS: With that in mind, let’s look at the typical ‘Cookie Marenco’ piano mic placement, using your mics on your piano in your room. Let’s say the musicians are arriving soon, you’ve never recorded them before, and you tell yourself, “I’d better get something ready.” How would you set up your B&K 4012s in that scenario, knowing that you’ll be fine-tuning the placement after hearing the player and determining the sound that best serves the music?

CM: Okay. The mics would be initially set up kind of like… [awkwardly attempts to demonstrate with a pair of pointed fingers]

GS: Are you showing me how to eat with chopsticks?

CM: Yeah, sorry! [laughs] It’s hard to describe. Ya know, the mics are still set up from a recent session, I’ll make some measurements now.

GS: Oh, yes please! While you’re doing that, I’m going to Google the 4012…

CM: Okay, here you go! The distance between the front of the microphones, from capsule to capsule, is 12 inches. The distance between the mics at the back is four inches. Those measurements are from the inside edges of the microphones. The angle between them looks a bit less than 90° but more than 45°. Maybe about 70°?

GS: Excellent information, thanks Cookie! While you were making those measurements I learnt that the 4012s are 6.89 inches long, which becomes the hypotenuse. Now it’s Pythagorus time! We’ve got a hypotenuse of 6.89 inches and an opposite of 4 inches. SOHCAHTOA says you’ve got an angle of 35.5° either side of centre. So you’re recording your piano with a pair of single diaphragm cardioids, capable of handling very high SPLs, spaced about 12 inches apart with a subtended angle of 35.5 + 35.5 = 71°. That’s very close to your estimate of 70°…

CM: I guess so! And I place them roughly above the middle of the piano strings. I have a seven foot piano – it would be different for a nine foot model, but for my piano there’s a number of internal structural bars on the frame and I avoid putting the mics over any of those bars because they tend to resonate. And I don’t stick the mics over any of the holes, either.

I try to get them pointing slightly down, so they grab the middle of the piano. I start about halfway between the lid and the strings, with the lid at full stick. Sometimes I’ll tilt the mic that’s over the bass end of the piano down a little bit to get more of the bottom end…

GS: You angle it further down than the other mic?

CM: Yeah, just a little bit. The mics aren’t necessarily parallel with each other. I’ll tilt that low end mic until it sounds good. I do that about 90% of the time because I can get a little more of the bottom end frequencies. The other mic usually has no problem getting the high end, so I don’t worry about it…

GS: So you’re bringing the proximity effect into the equation?

CM: Yeah. I use the proximity effect on the piano to get more ‘bass’ from that one mic. It’s a little bit tricky because you can overdo the effect if you’re not careful, but I like it. Also, I use angles a lot on all of my miking – especially guitar and vocals. I rarely point a mic directly at anything that’s giving off ‘air’ or sound. In most cases I’m always capturing sounds from slightly off-axis. It’s just a quirk of mine. [smiles]

GS: I’m guessing that’s also how you’re getting that harmonic detail on those low notes from the piano. The combination of the bottom end weight from the proximity effect, and the angling (which might be downplaying the fundamental and bringing out the detail in the harmonics of the low strings), work together to make your piano sound much bigger than would be expected for a seven foot model miked above the strings…

And right about now I imagine there’s a bunch of purists crying ‘blasphemy’ because your stereo pair is not strictly symmetrical. So, for their benefit, let’s go over it one more time… Why do you angle that low end mic down more than the high end mic?

CM: So it sounds good! [laughs]

PIANO PANNING

GS: Panning the piano is an interesting topic, similar to panning a drum kit. As sound engineers we really have to choose the most appropriate perspective for the recording. A pianist, while playing, always hears a wide and close image that pans smoothly from lows on the left to highs on the right. An audience member sitting somewhere in the middle of the front four rows listening to a grand piano centre stage in a recital hall gets a more distant and narrow perspective that is the other way around in the stereo image; the highs stay towards the left and the lows move towards the right. Meanwhile, an audience member in the front row of a small club watching a Modern Jazz ensemble (without amplification) will hear a narrow piano image that is almost entirely to their left side…

CM: Right! As we’ve already discussed, I pan the mics from the player’s perspective with low notes on the left side and high notes on the right side. I like how they separate that way, it’s as if you’re playing the piano. As a pianist, I don’t understand how anyone could pan it any differently!

GS: That’s how it’s panned on Heavenly Voices, and it’s quite consistent across the stereo image. I’ve heard — and admittedly made — many piano recordings that have what I call a ‘dancing image’ where the notes generally move across the stereo image, from one side to the other, but some notes jump slightly left when expected to go slightly right, and vice versa…

CM: That’s exactly when I start moving the mics around a bit, as we were talking about earlier. If the notes are jumping from left to right too much within the image, or I’m getting too much stuff in the middle, or the image is not pulling enough to the right or whatever, then I’ll make tiny adjustments to the mic positions and angles to fix that. I aim for a sound that’s balanced across the stereo image, so if the performer plays a scale all the way up the keyboard it would, ideally, create a stereo image that moves smoothly from left to right.

GS: Excellent! Releasing the sustain pedal now… On Heavenly Voices you’ve captured a very solid and round piano sound; the sort that audiophiles would describe as ‘visceral’. It’s quite close without being overly bright or ‘in your face’. What’s particularly interesting to me is that it doesn’t get the ‘munchy’ midrange sound I often hear when pianos are close-miked over the strings, which I suspect is due to reflections off the lid. You said earlier that you have the lid at full stick. Do you ever consider removing the lid?

CM: No, not in my room; I leave the lid on and open it up all the way. Also, depending on the player or what’s going on in the room, I might put a cover over it for isolation. I have a large black blanket that goes over it. Actually, I used the blanket on Fiona’s session with Rebecca because I was trying to get as much isolation as I could between the piano and the violin, but without needing the musicians to use headphones.

GS: Recording live in the studio without headphones is a topic I’d like to return to shortly. In the meantime, let’s get back to the blanket; I imagine it’s hanging from the lid to cover the open area around the curve of the piano body, so that it acts as an isolation barrier between the piano and the mics for the other sound sources – in this case, Rebecca’s violin and voice. Does that sound right to you?

CM: Yes, and for this session it was also hanging over the front between Fiona’s vocal mic and the piano strings.

GS: As we can see in the earlier pic showing the piano mics…

CM: Yes. Using the blanket to cover those open areas helps prevent some of the piano from bleeding into the vocal and violin mics. It’s far from perfect, but it does help for mixing. Also, my room is relatively live and has a lower ceiling than I’d like, so, depending on the performer and the music, there are times when the piano sound can contain more reflections from the room than I’d like. The blanket helps tone down those reflections; I often leave it on the piano even for solo performances. It’s a relatively cheap fix we discovered a while ago, and is a great trick for anyone recording at home with a low ceiling.

The blanket I use is actually more of a ‘comforter’; it’s kind of fluffy, polyester, and a few inches thick. And sometimes, when I’m not using it for isolation, I put it underneath the piano…

UNDER THE PIANO

GS: Oh, let’s talk more about that. I’ve done the same thing from time to time, and the reason I did it was to minimise reflections – perhaps even standing waves – between the piano’s soundboard and the floor. In any case, I think it improves the overall piano sound…

CM: Yeah. I’ll throw random stuff under the piano to absorb or disperse those reflections.

GS: Did you ever see that picture from one of Morten Lindberg’s 2L sessions where he had stacked small logs – presumably cut for firewood – on the floor beneath the soundboard to provide some diffusion?

CM: Really? That’s ingenious and it’s organic… I wanna start doing that! [Pauses thoughtfully.] You know, I don’t think I’ve ever had a conversation with anybody about putting things under the piano…

GS: Let’s keep it going… Can you give some examples of the “random stuff” you put under the piano?

CM: It depends on how much damping or dispersion is needed for the recording. It might be an unused guitar amp with some blankets or towels over it, it might be some boxes of various sizes, or maybe a length of carpet that’s been rolled up. I’ve stacked wooden chairs up just to add a bit of diffusion without absorbing the highs. All sorts of things. But it depends on the pianist, too, and what they’re comfortable with.

That reminds me… I often use the piano as a giant diffuser and musical resonator when I’m recording guitar or voice on the other side of the room. I don’t do the ‘brick on the sustain pedal’ thing anymore, but for years that was part of my repertoire. It’s a fun way of demonstrating overtones and sympathetic vibration to audio students! [laughs]

GS: A great trick! Do you remember what you put under the piano for Heavenly Voices?

CM: I don’t remember exactly what I used for that session, but I would’ve put something there and it wouldn’t have been the blanket because I was using that for isolation. Sometimes I’ll put baffles on the piano’s right side [player’s perspective] for isolation, but that wouldn’t have been appropriate for this session because I needed to maintain the eye contact and acoustic communication between the musicians…

VIOLIN MIKING

GS: This provides a convenient segue to recording Rebecca’s violin and vocals. Can we talk about what mics you used and how you set them up?

CM: Yes, of course. Now, in case you didn’t know, Fiona is a pretty powerful player…

GS: Actually, I did know that; I mixed Fiona live some years ago in a jazz club in Sydney, and she had Rebecca on stage with her! Fiona has a knack for sounding soft while playing loud – she’s a dream to mix live, but recording a violin in the studio alongside Fiona on piano must’ve presented some challenges. One of the smallest string instruments up against one of the largest…

CM: Right! Becky [Rebecca] is a joy to work with and, like Fiona, she’s an incredible player. She gets such a lovely tone from her violin, and I was experimenting with capturing it using two old RCA ribbon mics. I was trying a few of the standard ‘textbook’ mic placements, but then I decided, “You know what? I’m just going to go with what I hear. Where is the violin really giving me some sound?” Here’s a pic that shows how Becky’s violin mics were placed…

I often use the piano as a giant diffuser and musical resonator…

GS: Oh thanks, that’s a thousand words right there! What’s the model number of those RCAs?

CM: They’re BK-11As, the model that replaced the 44BX. They were made from ‘63 to ‘72, and were the last model of ribbon mics that RCA made – some say they’re also the best ribbon mics that RCA made. They were designed by Jon Sank, and this particular pair was re-ribboned and matched by his son Stephen Sank.

They’re on a long-term loan from an artist/engineer and his wife who bought them many years ago. They weren’t using them much and were followers of Blue Coast Music; one day they dropped in and offered to lend us some ribbon mics. I’m always hesitant to borrow that kind of equipment because I might fall in love with it or become dependent on it, and won’t be able to buy my own if or when they take it back! Anyway, I said ‘okay’ and I’m glad I did. I use them mostly on cello, violin and viola, and I’ve tried them on bass and also as a third mic for piano. They’re always interesting. We were also lent a few other ribbon mics to try, but these RCAs are the most fascinating in their sound.

GS: Nice! For Heavenly Voices you’ve captured Rebecca’s violin [a 1741 Castagneri with a bow from AR Bultitude] with a good sense of the instrument’s aged wood and ‘body’; it’s a warm and substantial sound from a small string instrument that could easily sound thin and piercing if not miked carefully. The tonality also sits nicely against your Steinway, which is a gigantic youngster in comparison.

CM: Thank you! [laughs]

GS: Do you ever use a Cloudlifter or similar in-line booster with the ribbon mics?

CM: I don’t. I tried using one long ago and didn’t like the sound. So I boost as much as I can from the preamps, and add gain somewhere else. So far, I’ve been able to eek out the sounds. Maybe I’ll try an in-line booster again one day, but I’ve got good preamps so I don’t really need it.

GS: Those RCAs are bidirectional, which means the one that’s placed to the side of the violin was probably rejecting a lot of piano spill with its side nulls but the one in front of the violin had its rear lobe facing the piano strings. No wonder you needed the isolation blanket…

VOCAL MIKING & ISOLATION

CM: Yeah. So I had the two RCAs on the violin, I did my usual miking on the piano with the B&K 4012s, and then I added the blanket, as we’ve already discussed. And then there were the vocals that we were doing live, which is always tricky because the piano is going to spill into the vocal mics. Becky did most of the vocals; there were occasions where Fiona was doing backup vocals and maybe a few leads, but mostly it was Becky singing in between playing the violin parts – all live in the studio.

GS: And all of this was done with no headphones, so therefore all at close range to each other for maximum communication. What a fabulous challenge!

CM: Yeah! Everything is happening live in the studio. I’ve got mics for piano, violin, Fiona’s voice and Becky’s voice, and I want to set up the two players so they can interact and hear each other comfortably without wearing headphones.

GS: So you put up additional mics for Rebecca’s voice rather than relying on that front violin mic, which looks reasonably well placed for her voice as well. What mic did you use for Rebecca’s voice?

CM: I started with couple of AKG 414s. Of late I’ve come up with this technique I call ‘the backup plan’ using two 414s. I put one wherever I can grab a good vocal sound – it’s never right in front, it’s usually at eyeball level. I make the decision on the mic placement depending on the motion of the performer – I watch how they move when singing, and I try not to constrain their natural movements by making them focus on singing into a microphone. So the mic placement is usually based on movement as the first consideration. It’s not always the same. And then I have another one that’s placed behind it, which is the backup mic in case the closer mic gets blown out on a loud note. Those two mics can sometimes be at odd angles with each other, as much as 180°, and a lot of times at 90°. I use the Ouija technique of placement – whatever sounds good. [laughs] A lot of very odd phasing can happen with this approach, of course, and I have to be constantly aware of that. Usually only one mic ends up being used in the mix, with the other edited in when needed. It can change from song to song, depending on which mic sounds better and most appropriate to the music and the performance.

On Heavenly Voices I started with the two mic ‘backup plan’ 414s on Bekky’s voice, and had a Tannoy ribbon mic set up for Fiona’s voice. I wasn’t liking the sound of the Tannoy – it sounded okay on her voice, but it’s not one of those mics I regularly pull out simply because I love it! [laughs] So I quickly moved one of Bekky’s 414s to Fiona’s vocal position – as you can see in the pic below.

GS: Oh, that’s interesting. Earlier I mentioned that I mixed Fiona and Rebecca live once. I’d been told in advance that one of the performers (Rebecca) was a soprano who played violin and sang, and I was wondering how I was going to mic that combination in a sound reinforcement situation. I was assuming she would ask for two microphones, and that would mean I’d have to be watching her constantly – riding faders and muting mics to avoid all the spill, comb filtering and feedback possibilities that such a two-mic setup would present. But when Rebecca showed up she asked for a single microphone and tapped her finger on a spot in the air very similar to where the 414 is in your pic. Skeptical but willing to try, I put a Milab DC196 there and Rebecca did all the work for me after that.

That’s a lesson I’ve learnt many times – when confronted with an unusual instrument or combination of instruments in a live performance situation, you can often bypass a lot of headaches by starting with the mic placement the performer suggests…

CM: Ya know, being a sound engineer is a bit like being a fireman – sometimes you’ve gotta throw down the hose, pick up a hatchet and bust up the building. You don’t think too much, you just do it! [laughs] It has to become instinctual. If there’s a problem, solve it fast. The most important thing is keeping the performers happy.

GS: Right! Getting back to the recording setup for Heavenly Voices, you’ve ended up with a lot of mics in a relatively small area…

CM: Yes, because the musicians need to be close together for this kind of ‘recording live without headphones’ approach. Seeing and hearing each other properly in the room are both very important considerations for the musicians. So the first thing I do – even before I set up any microphones – is let them play together in the room for a while, let them find where they’re the most comfortable. Then it’s up to me to get the sound from there.

GS: [adopts authoritative voice] Do your job!

CM: Yeah! [laughs] If you haven’t already guessed, my approach to recording is much more from the musician’s standpoint because that’s my background; I’m a musician. I never aspired to be a sound engineer. I have great gear, but that’s because I want things to work and sound good. I’m not a ‘gear head’ – I barely remember the model numbers of my gear! [laughs]

So I relate to the musicians in this recording environment. I try and set things up so that they can perform at their best, and so that my role is more ‘invisible’. It’s the fine art of sonic negotiation between the musicians, their instruments, the room, the mics and the gear – all with the goal of capturing a great performance.

In ‘recording live without headphones’ sessions like this everything is going to bleed into everything, so there’s a balancing act going on. I just negotiate with the mics, the players and the faders to make it all work. I’m listening to it all through my analogue console, and I’m always moving faders around and checking how things are going to sound when mixed together, checking what happens when I add some reverb, and finding out ‘what if I do this’ and ‘what if I do that’? So if things are obviously not working I can make adjustments on-the-spot – before it goes too far and gives me problems to fix in the mix…

GS: So you’re monitoring from the perspective of the finished mix, as opposed to focusing on recording things as clean and separate as possible and hoping you can make it all work together later. It’s a bit like the two-mics-direct-to-stereo approach, but with the benefits of individual mics and multitrack recording…

CM: Yeah. When recording everyone performing live in the same room without using headphones, you really have to work that way.

GS: I’m a big fan of that approach. It keeps things in perspective; getting on with the recording rather than obsessing over, say, a little bit of spill that’s only audible when soloing an instrument because it simply doesn’t matter when heard in perspective with the mix…

CM: It changes everything, but, you know, the ‘recording live without headphones’ approach doesn’t always work – especially if there’s too much emphasis on getting a great sound but not enough on making the musicians comfortable.

GS: I can think of a few audiophile recordings that might fit that description…

CM: Don’t get me started! I’m not going to mention any names but I know of other ‘recording live without headphones’ sessions where the musicians have been placed in the room to optimise the balance rather than optimise their performance, especially when working with direct-to-stereo techniques. So they’re in a big space that sounds great, maybe an old church or similar, but they end up with the drummer way down the back of the room because the drums are too loud, meanwhile the double bass player is up real close to the main pair of mics to get it loud enough, and the saxophonist is somewhere else off in the distance – and all of this has been done so that the balance is right in the stereo pair. There’s no real interaction between the musicians because they can’t hear or see each other properly. The sound quality might be great, but the performance isn’t.

Long ago I decided that what I do is not about sound quality; I mean, sound quality is not my primary goal. Performance is my primary goal. I want to capture a great performance, even if that means I have to sacrifice some of the tone or work a bit harder…

GS: In other words, so that you have to… [inhales deeply for effect]

GS & CM in unison: DO YOUR JOB! [laughs]

I never aspired to be a sound engineer.

SIGNAL PATH & MIXING

GS: You just said that “sound quality is not my primary goal” and yet you’re using excellent equipment, you’ve been championing the DSD format for some time now, and you build your own silver/copper cables! No wonder Blue Coast Records is considered to be an audiophile label… With those things in mind, and with the all-important microphone choices and placements out of the way, can we talk about the rest of the signal path for Heavenly Voices?

CM: Sure. The B&K 4012s and the AKG 414s went into the Millennia Media HV-3D-8 preamps. Although Millennia offer a high voltage mic input option on their preamps, I use the high voltage power supply that comes with the 4012s. The RCAs went into some vintage Neve preamps. They came from an old Neve console and were made into strips. They were rebuilt by Brent Averill Enterprises (BAE) and are fantastic.

GS: I count six mics so there would’ve been at least six tracks, yes?

CM: Six to eight tracks – we added backing vocals to some of the pieces.

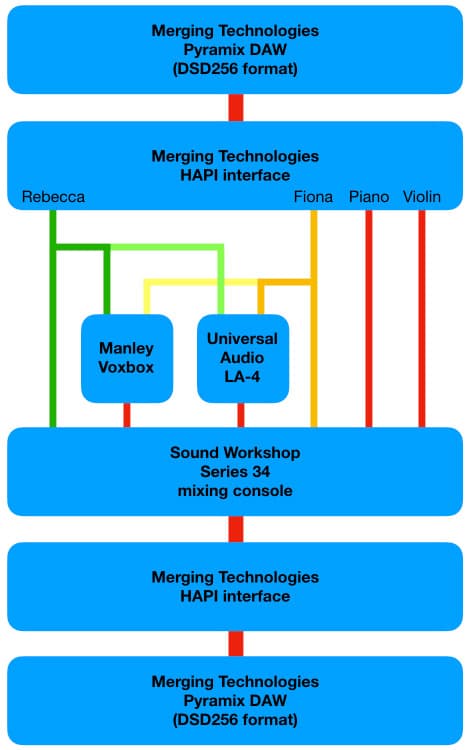

GS: Which brings us to multitracking… As I understand it, you tend to treat the DSD recorder as an analogue multitrack recorder, preferring to do all the mixing through your analogue console.

CM: Yes, I do…

GS: Okay, tell me about your mixing console and outboard…

CM: The console is a 48-channel Sound Workshop Series 34. I have a lot of vintage reverbs: there’s an AMS RMX16, a Lexicon 224XL which I love, and I also use a Lexicon PCM42 as a predelay into a Lexicon PCM60 reverb – it’s a good combination. Neil Young used to rent that PCM42/PCM60 combination off me, along with the 224XL, by the way!

GS: Knowing how strongly Neil Young feels about sound quality, I think that’s a pretty good endorsement for those processors. Did you use any compression or other dynamic processing in the mix?

CM: I used no compression at all on the piano or the violin. For the voices I used a Universal Audio LA-4 and a Manley Voxbox – most people use it as a preamp but I love the compressor part. I run them in parallel on their own channels, sending the source to them through a bus rather than inserting them on the channels, because I find there’s always a loss of low and high frequencies when compressors are inserted directly into the signal path. I stopped using them that way a long time ago – except for rare cases.

I’ll generally feature one compressor for each voice, but add a small amount of the other voice to adjust the sound. So for Heavenly Voices I might have featured Becky in the Manley but with a little bit of Fiona going in there as well, and I might have featured Fiona in the LA-4 with a little bit of Becky going into it too.

I have other compressors… There’s an Aphex Compellor, and two of Millennia Media’s Origin channel strips, which have good compressors in them – sometimes I use the Origin to add just a touch of subtle compression before going into the LA-4 or the Manley. It offers a very light touch, and sometimes – but only in real emergencies – I’ll use it in parallel on piano.

I’ve got two strips of Dyna-Mite compressor/gates and two strips of Gatex noise gates, I don’t use them any more. I always hated the gated snare thing, but I did use them delicately to cut hum/buzz from guitar amps when I could. I don’t need to do that any more with digital recording, of course. Ah the memories!

Mixing is like performance art to me; it’s like sitting behind a big Ouija board and sometimes, seemingly out of nowhere, I’m pulled to create the vibe on the fly. Seeking chills, ya know?

GS: Oh yes, I know those chills! It’s important to recognise them and then save or capture that mix immediately; there’s always a temptation to fix one more little thing, but the moment you change anything the chills go away and they never seem to come back again… So, I’ve learnt to capture those mixes when they’re working, even if the balance isn’t exactly what I want.

CM: With the ‘recording live without headphones’ work that I do there are times when everything is bleeding into everything else. I do what I can with isolation and I’m constantly checking during recording to make sure I’m capturing something I can work with, as we’ve already discussed. Sometimes the spill from the piano into the other mics means I can’t lower the piano volume quite as much as I’d like to, or perhaps I can’t bring a vocal up as high as I’d like to because it brings up the piano spill. So I do the best I can. Sometimes I’m able to create an illusion and make it all nicely balanced, other times the balance is not exactly as I’d like it but the chills are there – the performance is there, the mix represents it, and I’m getting those chills. So we put it out…

GS: I have often said that nobody except sound engineers and audiophiles buy recordings simply because they sound good. A reasonable recording of a great performance will sell far more than an excellent recording of a poor performance.

CM: Exactly!

GS: Speaking of capturing the mix, let’s talk about your converters and DAW…

CM: I have Meitner converters coupled with the Sonoma DAW, which sounds fantastic. I really like the sound of the Meitner converters, but the Sonoma rig only records to DSD64 and I wanted to use DSD256 for Heavenly Voices so I used my Pyramix rig with the HAPI interface and its high resolution cards…

GS: Oh, both great sounding rigs! What do you mix down to?

CM: We’ve set up two inputs on the HAPI and two tracks on the Pyramix to capture the analogue mix back to DSD256.

THE DSD CONNECTION

GS: The old school analogue part of me is getting the warm and fuzzies at the thought of this – all the lovely sound of analogue without the hiss, saturation and other non-linearities of analogue tape. Tell me about your connection to DSD…

CM: My connection to DSD was… Well, it’s a long story!

I used to fly up to Boulder to do my mastering with David Glasser at Airshow Mastering, and a guy called Gus Skinas had his studio right next door. We became friends partly because of that and partly because in the early days of the ‘80s – when digital recording was first coming about – we both worked with a guy named Gerry Kearby who had a company called Dyaxis [later bought out by Studer]. Gus took a job with Sony and was part of the team that designed and built Sony’s Sonoma DAW for recording, editing and mastering of DSD, and for authoring of SACDs. When I told Gus I was going to experiment with a new kind of surround recording, he offered to bring along the Sonoma DAW.

I’d invited a bunch of great musicians to a studio across from Skywalker Ranch called ‘The Site’ for these experimental surround recordings. The control room’s monitoring was set up in the ITU 5.1 surround configuration the entire time. Each day was a different group of musicians who would thankfully play for long hours while we tested microphone placements, cables and formats for this new type of surround sound we were creating, which eventually became our ‘Extended Sound Environment’, or ‘E.S.E.’. During those sessions we compared analogue tape, DSD64 on the Sonoma, and 192k PCM on Protools. My co-producer, Jean Claude Reynaud, and I decided that the DSD64 recordings sounded far better than the PCM recordings, but analogue tape was still a little more to our liking. PCM seemed to lack the true high end and low end when compared to DSD, especially on acoustic instruments. Also, the dynamics of DSD were much better. You could really hear it with the acoustic guitars we were recording…

Anyway, after a few days of these sessions Gus said, “This music is fantastic! I hope you’re going to make a record!” “Sure!”, I said, full of confidence, but – truthfully – I was kind of stunned. I hadn’t even considered making these recordings into an album until Gus mentioned it. They became the first Blue Coast Records album, the ‘Blue Coast Collection’. It’s an SACD with the surround layer from the DSD surround mixes. We did the two channel stereo mixes to half-inch analogue tape, and the surround mixes were captured in DSD. Immediately after those sessions I got a Sonoma DSD system and I’ve been using it ever since. I also have a Pyramix system, as we’ve already discussed, and some other DSD recording devices from Tascam, Korg and Sony.

GS: I actually have that first Blue Coast Collection disc – it was part of a collection of SACDs I regularly used to demonstrate DSD and dynamic range to my audio students. It’s the one with that little whispered monologue at the end that comes out of nowhere like a bonus track, something about finding a ball of fuzz, right?

CM: That’s the one! Glen Moore had recorded a short piece for solo bass and we thought we’d add the ‘surprise’ after about 45 seconds of silence. It was Garett Brennan whispering that little story about the ball of fuzz. Almost every album now has some talking at the beginning or end to bring the ‘human’ sense of the studio into it.

Mix magazine did an article on those sessions back in… 2004! Where did all that time go?

GS: I wish I knew, Cookie, because I’d like to get some of it back! On that subject, we’ve been chatting for quite a while now and we probably should finish before it gets too big for the magazine. Do you have any closing comments?

CM: Well, okay… Ya know, a lot of things have changed over the years but the one thing that hasn’t changed is listening. Whether carefully listening to the sound of nature captured through a microphone, recording an artist’s requests – spoken or unspoken – or whatever, capturing sound and music is preserving history. There is always something new to learn and listen for.

GS: There is indeed, Cookie! Thank you for your time, tips and insights, it’s been wonderful chatting with you…

CM: You’re welcome! I like talking to people who understand sound and can talk about a Hamburg Steinway versus a New York Steinway. Oh, and also, try not to bump into the piano on your way out – I’ve just cleaned it.

That’s one of the most in-depth tech recording interviews I’ve ever read. Really xlnt. Deep layers of experience and know-how. Should be required reading for recording schools and seasoned pro’s alike.