Feeling Good: Michael Bublé Live

He’s one of the biggest touring acts in the world and the audio production one of the most highly finessed.

‘A mix is a mix is a mix.’

This is the sage advice given to FOH engineer Craig Doubet by a recording engineer mentor David Leonard (who won a Grammy in 1983 for co-engineering the Toto IV album). By which he meant: a good mix will translate across any monitoring system. Craig carried that lesson into his live sound career. In a live context, the lesson is: make sure your well-balanced mix sounds good in the room by getting your PA right — right design; right tuning.

Which is why Craig Doubet personally oversees the intricate Michael Bublé PA design. He knows most of the arenas in the world pretty intimately and armed with Meyer Sound’s MAPP acoustic prediction program, will make sure his crew chief knows exactly what the PA design will be as they back the trucks up.

And what a PA it is.

MEYER: L OF A PA

The Solotech-sourced PA is entirely Meyer Sound and mostly ‘L Series’ with some Mica. A 200+ box Meyer PA is always awesome to behold but the special sauce is in the use of a Meyer Spacemap beta that allows Craig to move Michael Bublé’s vocal image down the room when he ventures onto the catwalk to the B stage. The design introduces additional arrays that carry only the vocal and help localise Michael’s vocal when he’s on the B stage. I’ll allow Craig to explain further:

“Michael started using a B stage about 10 years ago. He loves it — he loves that connection with the audience. On the last tour, we had a large B stage surrounding the front of house mix position and we even had punters inside the stage — it was a real feature of the show. But depending on the venue, the B stage/FOH position could be as much as 60 metres from the front of stage. As you can imagine, that’s introducing quite a delay between him and the output from the FOH PA.

“Michael uses IEMs but he also uses a set with ports to get an ambient feed into his ears. What’s more, in that previous tour’s show the B stage at times featured a full band with seven open microphones. All up, this was introducing quite a slap off the PA compared to his ears. If you’ve never tried to sing or talk with a 100ms-plus delay, let me tell you: it’s not easy. I don’t know how he did it.

“He always asked what we could do to fix it and really the only answer was: hang another PA. Which was never going to happen in the middle of that tour.

“For this tour, we had a shot at addressing the problem.

“This tour’s stage design sees a large bandshell and a long 30m thrust ending in a 10m-diameter B stage. Just like last time, he loves it and is always on the runway.

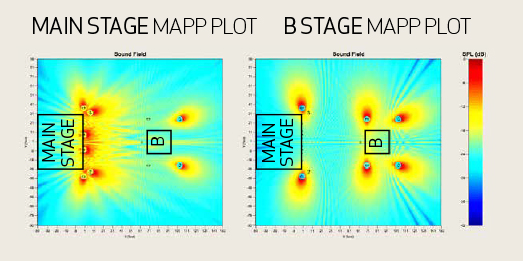

“So my design goal was: ‘How do I cover the room without aiming any speakers at that thrust and that B stage?’ First up, I place two main hangs in the room where the B stage ends, which covers the back of the room. The advantage of that is, now I’m not throwing 100m with a main PA, I’m throwing a maximum 65m into the back seats. So right away I’ve just decreased the reverberation distance in the direct field.

“Next, we took a fresh look at what I’d have previously called our main hangs. This time I’ve got them pointing away from the centre of the room by about 20 degrees to keep their dispersion away from the thrust. Next to those is another hang that points straight out sideways. So between those three hangs aside, we cover the entire room.”

B STAGE PA

Where it gets a little trickier is when Michael comes right out to the B stage. To avoid the issue of the last tour where Michael was hearing himself from the main PA 100ms or so after he’s singing into the mic (and hearing himself in his IEM), Craig takes the vocal out of the main hangs.

More than that, to ensure the audience isn’t losing any of the vocal and hearing the vocal localised at the B stage (rather than a mis-match of hearing the vocal emanating from the main stage), two additional arrays are brought into play — one that fires back at the audience from the B stage and another that fires sideways.

“So essentially his voice is moving where he physically is,” explains Craig. “Everyone still gets his vocals. It just changes perspective. If you’re sitting to one side, you feel the vocal shift because it’s removed from the FOH PA and goes to the side hang in the middle of the room.

And that’s how we are using Meyer’s Spacemap on the Galaxy matrix.

“Meyer built me an interface and a program that’s a virtual fader on an iPad. It has one job to do: to move Michael’s vocal back and forth. It was an enormous amount of work to set up but is now easy and reliable to use.”

SPACEMAP BETA

Most of the time Craig is ‘panning’ only Michael Bublé’s vocal up and down the room. Does the vocal slide a little with the timing of the rest of the mix? Yes. But as Craig points out, that’s not such a big deal for this genre (just listen to some old Frank Sinatra records to hear how elastic the timing of the main vocal can be).

At one point in the show, though, Bublé plays an ‘intimate’ club set at the B stage with a small band. At this point the whole B stage band is being reproduced through the B stage PA, with nothing coming out the FOH PA.

Of course, Meyer has been doing this kind of sound design gymnastics for years, working with musical theatre and Cirque du Soleil on some amazing immersive audio productions — mainly using its DMitri platform. But this was taking the Spacemap software and applying it to the Meyer Galaxy matrix. “It just made life easier,” recalls Craig. “We didn’t need to get another piece of gear involved into our control rack.”

SSL MIXING

The latest tour saw an appreciable increase in the number of inputs from stage, and Craig Doubet was looking to upgrade his mixing console as a result. He decided on a SSL L500 Live. He explains why:

“I’m an SSL user from way back when — 1985, in fact, with the E series and G series studio consoles. When SSL came out with a live console they contacted me to see if I was interested in taking a look. I liked what I saw and took a console out with Selena Gomez a few years back — learnt it and loved it.

“The first thing I noticed is it sounds good — it sounds like an SSL to me, and that sound is in my DNA. Because I’m so familiar with the sound, it performs entirely predictably for me — when I tweak that pot it does what I imagine it’ll do to the sound.

“The preamps are amazing. They are super clean, and have super high dynamic range. I run most of my inputs really hot and they sound amazing.

“The layout of it appeals to me as well. There’s always at least three ways of achieving something and you get to choose your favourite way of doing anything. When I go back to other consoles now, I feel limited — ‘oh, there’s only one way of doing that?’.

“The L500 console compression is great. The channel compressors are a model of SSL’s classic console compressors with all the controls you’d expect on a pro console. Then there are three onboard plug-ins available, which are amazingly beautiful. There’s the bus compressor SSL built for the E Series consoles that every mix engineer loves. SSL’s talkback compressor also comes from that E Series console, and remains the benchmark comp if you want to trash your source.

“I also run a couple of compressors from a Universal Audio Live Rack that runs seamlessly via the console’s MADI I/O.

“I have moved away from using a lot of external effects. But, then again, UA produces beautiful renditions of its own compressors. So I’ll always use an 1176 on the upright bass, for example — nothing else sounds right to me. And I’m using a beautiful version of an LA-3A on Michael’s vocal — it’s super fast and works amazingly well live.”

VOCAL CHAIN

Michael Bublé’s vocal signal chain starts with a Sennheiser 6000 Series microphone with a Neumann KK204 head. The 6000 system digitises the audio in the transmitter. The audio from the receiver goes straight to the SSL stagebox via AES and then splits to the two Digico SD7 monitor consoles — all consoles take the signal digitally. Once the vocal hits the SSL L500 Craig uses the console’s flexibility to massage it into shape.

Craig Doubet: “One of the cool things about this SSL console is you can reorder the channel structure. In the case of Michael’s vocal I put the high-pass filter at the top and then a dynamic EQ. From there I apply an external EQ compressor de-esser, then the channel EQ and the channel limiter, which is there just in case.

“The dynamic EQ does most of the legwork. I started using the BSS DPR901 [dynamic EQ] around 30 years ago and the SSL dynamic EQ serves the same purpose. It’s not so much of a de-esser in this case as a way of evening out the proximity effect when Michael moves his mic around — and he moves it a lot. He’s also a very loud singer; he’s got a big voice and can get away with moving his mic more than most people but I need the dynamic EQ to even out the frequency response.

“The channel EQ is just notching out a few frequencies. Michael still uses floor monitors and some sidefill as well as IEM so there is some ‘ringing out’ of certain frequencies.

“Overall, I try to keep the vocal as clean as possible. My starting point is to ensure Michael’s vocal sounds like Michael Bublé.”

Craig then applies some light use of reverb to the vocal — a Lexicon 224 emulation and an EMT250 plate reverb emulator. “I love the EMT 250 because, to me, it’s always worked on a male voice. It’s not so much a reverb as a sense of space. It gives you some nice balance at the bottom register of the voice.

“I have both effects in there all the time. Their proportion varies depending on the song.”

MIX TECHNIQUE

The Michael Bublé show is essentially the same format as the Rat Pack shows of the ’50s and ’60s. Michael is the raconteur with the ‘amazing pipes’, charming young and old. It’s a show with potentially dozens of open mics, featuring some pin-drop detail counterpointed by huge orchestral hits. It’s a mix that requires painstaking preparation and finesse. Craig Doubet explains:

“I reckon every live sound engineer should sign up to a Hippocratic oath: ‘do no harm’. That’s my first responsibility, to do no harm to the music. I like to keep it clean — every input is as clean as I can make it. I get rid of any extraneous frequencies or bleed as best as I can. Or if bleed is unavoidable, I’ll use it. For example, I have 16 mics on strings, surrounded by reflective surfaces. As a result, I’ve learned that as I bring strings up, I can reduce the vocal FX send, because those mics are acting as an introduced ambience.

“In songs where the strings or brass aren’t playing, they’re muted in a console snapshot. Some snapshots even have some level changes. Anything I can do to reduce bleed and have an unnecessarily open mic, I’ll do that with a fader move or a snapshot.

“Every instrument has some compression. Sometimes to just save my skin in case of an unexpected level change, while at other times to help deliver that traditional big band sound.

“Audiences have an expectation of what a big band sounds like, stemming way back to those original vinyl recordings from the 1940s. Those pressings had quite a limited dynamic range, so you need to replicate that somewhat to make match expectations.

“That said, thanks to this huge band, I’ll have 30dB jumps in level on occasion. It provides great impact and that’s what Michael wanted — he wanted the band to impact people; for there to be a real sense of power.

“Above all, it’s about making sure the audience hears Michael Bublé. I constantly ride his level and ensure he’s sitting high in the mix. The beauty of this style of music, is when the band is really going for it, that’s not when Michael is singing, so I rarely have to choose between Michael and the band in the mix.

“When I mix, I’m totally dialled into what I’m doing, and I get physically involved. I like to put some emotion into what I do.”

Great article folks. Wish I’d seen the show now.