Home Grown: Paul Mac & Andy Rantzen

19th Century German poets and chance meetings with rap artists in New York can result in some favourable outcomes. Not to mention throwing everything you know about collaboration out the window. Paul Mac and Andy Rantzen talk about their love affair with fortuity.

Back in the 1980s, the world experienced the birth of a completely new musical phenomena. Punk had seemingly run its course and the world was growing weary of guitars and rock. The breakthrough genre was a cacophony of trance-inducing music, composed entirely from electronic instruments such as drum machines, samplers, synthesisers and sequencers. The inspiration had developed from sounds forged by acts such as Kraftwerk and the quirky 1970s disco culture. It was stark, simple, and brash.

The movement had started in mid-1987, taking its lead from the acid-house movement and tracks such as Steve ‘Silk’ Hurley’s TR808-infused Jack Your Body. A couple of British club owners had spent their summer in Ibiza, and had, in turn, introduced friends and DJs, Paul Oakenfold and Danny Rampling, to the hedonistic mixture of ecstasy and electronically produced music. The guys thought it was a rapturous way to spend the night, and when Danny returned to London, he opened a club called Shoom, closely following the Balearic islands theme established in Ibiza during the summer. In fact, it was Shoom that first used the yellow smiley face logo on promotional flyers. By the very early ’90s, the rave concept had infiltrated Australia, and a few English ex-pats were organising parties every second weekend or so. At the time there were countless unused warehouses around Sydney, so it wasn’t hard to find a large space in a semi-industrial area on the cheap, install an incredibly large stereo PA and a bunch of lights, and get stuck into it for the night. With a regular following of around 1000 punters at 20 bucks a head, it was a lucrative proposition for the entrepreneurial DJ. Inevitably, the lawmakers got wind of these ‘private functions’ and began a gradual crack-down, but in the wake of all of this – and also due to the higher profile of electronic music as a genre – Australia’s own breed of electronic music artists began realising greater popularity. One such act was Itch-E and Scratch-E, who made their debut at one of Sydney’s seminal outdoor raves – Happy Valley 2. This gig was the first to host Paul Mac and Andy Rantzen’s slant on electronic auditory hedonism, and the early morning time-slot saw the first airing of an amiable little tune by the name of Sweetness and Light. The track went on to win an ARIA award for the pair – the presentation featuring the somewhat notorious incident where Paul thanked Australia’s ecstasy dealers during his acceptance speech. Perhaps not so politically correct, but it certainly made it clear who the listeners were. Fast-forwarding through the remaining ’90s, we witnessed Paul Mac enjoying what he describes as “a modicum of success,” acting as producer and remix guru for a number of acts including Silverchair, Powderfinger, The Mark of Cain, Grinspoon, The Cruel Sea, INXS, Placebo, and of course, his own inimitable brand of electro exploits with Daniel Johns and Presets members, Julian Hamilton and Kim Moyes – The Dissociatives. Quite a journey from the early days with Itch-E & Scratch-E cohort, Andy Rantzen.

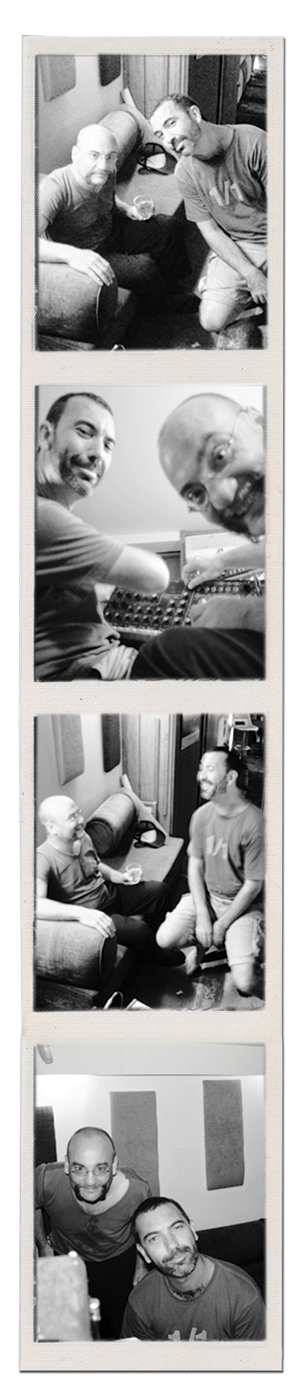

Recently the pair rekindled this early relationship, with their management no doubt drawing upon the recent 20-year turnaround and interest in early ’90s dance music. That’s not to say the pair are attempting to ‘cash in’ on the current electro craze, as you’ll see from the following interview. I caught up with the pair at Paul’s Panic Room studio and as the evening advanced into the wee small hours, the three of us discussed things like: just what was it that made the two tick when it came to producing their inimitable electro stylings, and how do you remain progressive in such a saturated market?

SCRATCHING AN ITCH

Brad Watts: So how are you settling into Paul’s Panic Room, Andy?

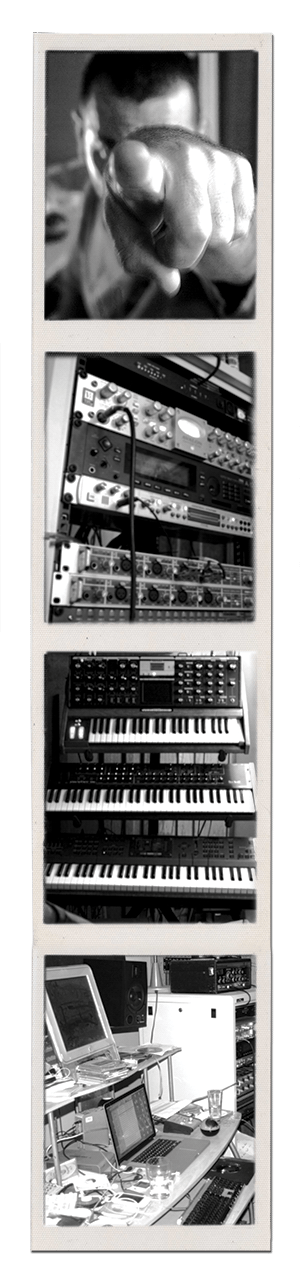

Andy Rantzen: Well, I’d have to say that the one thing I dislike about modern studios, including Paul’s, is that there’s no mixing desk. It’s the funnel that channels everything down. Paul and I found a way around it but we both miss it a lot. No desk, no knobs… it’s like the pot you cook the dinner in, but in this case there’s no pot. It’s just the way technology is going, I guess. People miss analogue tape as well; but that’s mostly gone too now. And in my experience musicians never really talk about this or understand it; it’s something you hand over to engineering guys really.

BW: Meaning?

AR: Well, someone like Paul, or many of his colleagues and people he knows, know about the esoteric world of what happens after the mix, what happens in the desk, the technology and the electricity and how it all works together – exactly the stuff AudioTechnology magazine focuses on. That world is very outside where the magic really happens for me.

BW: So Paul, what moved you in the direction of electronic instruments rather than sticking to, say piano and keys?

Paul Mac: Well, I kind of took over every other band I was in. It was like a coup every time, which I got quite tired of. The move was certainly due to technology. I used to go to Venue Music where they had a Roland TR606 and an SH101 on display. I had no money so I used to go in there with a set of headphones and just write a song. I remember thinking, “Oh my f**king god, I am master of the universe!” I was actually in control and could do anything I wanted.

The 101 had a 64-note sequencer that you could trigger from the 606 and I eventually worked my arse off at McDonalds and bought it. Then I realised it had two trigger outputs so I bought a Roland JX-3P which had a 128-note sequencer. At that point I had the bass and drums covered, so it was like, ‘sorry band, I’m taking over’.

Suddenly there was no need for a drummer. You know that guy that’s always annoying you to get his reggae track into the set? (Laughs) The music seemed to bloom right there in your hands without having to deal with anybody! I could have a vision and create it on my own or with one other person, so suddenly the machinery represented freedom for me. You just got a bass synth and went for it.

BW: Sure, but you were an accomplished musician as well of course; you’re a great player. It’s presumably relatively easy for you to pull stuff like that together.

PM: But still, for me, the revolution was Kraftwerk and Public Enemy. Up until then I’d been listening to Rick Wakeman where the more notes and faster you could play the better musician you were. When those two acts came into my sights it changed everything for me, and that’s how suddenly people like Andy and I became musical ‘equals’. Plus, at the time, I remember music suffering a real split. There was the paisley shirts faction and that whole ’60s vibe, which really horrified me. I remember thinking at the time: “Have you not heard Kraftwerk? Why are you replicating something that’s been done before?” For me, the idea of futurism was always the answer.

BW: What brought you two together then? The Evening Star days? I remember that’s where I used to see the Pelican Daughters and The Lab [Andy and Paul’s respective bands at the time. They played in one of Sydney’s premier alternative pubs during the ’80s – the ‘Evil Star’].

AR: …a Pelican Daughters album actually, although we’d met briefly before then. We’d met once or twice and I remember Paul saying we should do something one day – that was about 1989. But I honestly didn’t think we’d do anything.

PM: Once again I shovelled my way in. Andy wanted to borrow my mixing desk. One gear-swap led to another and it was like: ‘You’ve got a 303? Cool! I’ve got an 808, let’s sync this stuff up and do something’. So we eventually combined gear and got something happening.

AR: And about this time we both started getting into acid house (this was slightly before techno) – but none of our bandmates or friends were. So eventually they all drifted away because they didn’t like what I was doing. As far as we knew there were only two people in Sydney that wanted to play dance music with a twist. We’d been doing obscure stuff for years really. The Pelican Daughters was going since ’84, and The Lab and Smash Mac Mac went back to ’83. So we’d been around and had a few bands before we started working together.

I think the edges have washed off us both. We’ve become more like pebbles and less like jagged rocks.

SYNERGIC EFFECTS

BW: What’s made the relationship so beneficial in a musical sense?

PM: Well, Andy has always got ideas, and I know how to make them happen. I don’t always know if my ideas are as good as Andy’s, but together we’re quite useful.

AR: Yeah, often I’ll think of something, and instead of trying to play it, I’ll just sing it or do it with my mouth and Paul fills it out.

BW: Yeah I was quite surprised when you were explaining the notes in Sweetness and Light to me – you sang them in what sounded like perfect pitch.

AR: I don’t have many talents, but one of them is that I can hear things very clearly, and another is that I know who’s good at what, and really, that’s all I rely on.

BW: Has the way you write music together changed much over the years?

PM: Well, we actually had an argument last week about the final track on the new album – Andy wanted to change it, and I loved it just the way it was. Years ago we would have had a massive argument about it. These days it’s a case of, unless both of us whole-heartedly agree with the track, it’s not going on the album.

BW: But you’re both comfortable enough with each other to have that stoush.

AR: Well, that’s just the thing. It wasn’t a stoush this time; it was more of a ground-giving exercise. I think the edges have washed off us both. We’ve become more like pebbles and less like jagged rocks. I tell you what the difference is – and back then the stoushes did happen – I would have become more and more cross in my mind, creating completely imaginary dialogues and getting angrier and more upset. Then, by the time I’d have rung Paul, I’d be in such a state that I’d be angry and aggressive from the start. Nowadays we’re a little older and we understand how each other works.

PM: I think in the early days we both felt undervalued by the other. Back then, to me they were my musical notes, and Andy would be like, “But that was my idea!” Of course, I’d be like, “But mate, I made it happen!” It was just a nightmare. Nowadays, it’s way more like, “Great idea, I’ll make it happen.” I think we recognise each other’s skills now and we’re comfortable working with that.

It’s all about finishing each other’s sentences musically, which I reckon I’ve only experienced with two people in my whole career. One is Andy, the other is Daniel Johns. It’s exactly the same level of communication.

BW: Dare I ask if anyone prompted you to get Itch-E and Scratch-E back together? No cajoling from your management?

PM: No, I think Andy was way more vigilant about our legacy than I was for a long time, and he really protected that eventuality. There have been plenty of opportunities to cash in on our older material – plenty of times when I’ve had DJ’s or producers begging to do a remix of Sweetness and Light for instance. Andy always stuck to his guns and said: “No f**king way!” and I was always like, “fair enough.” Then these rave reunion type shows started coming up…

BW: So why were you so against it Andy?

AR: I was just being pig-headed really. I thought we needed to create some space and time around it – leave it alone for a while without polluting it. Then I had a kid, got divorced, got bored, had a new relationship, rent in Sydney went up, and I started thinking, ‘Actually, this is my job as well’. So, in retrospect, it was probably a moment of weakness. It’s more about whether we wanted to leave this alone, or take it somewhere fun and meaningful.

PM: Actually, I think it was even lazier than that… not that I’m discounting Andy’s comments. But the fact was we simply didn’t (and don’t) have our Ensoniq samplers anymore, or the floppy disks or the multi-tracks for Sweetness and Light. In order to do anything we needed to sample the stereo masters and try to rebuild something out of that. The amount of effort involved in that made us decide to simply make some more music. To do a rave set was ridiculous.

We did try and recreate some of it at one point, but it was just so boring filtering out kick drums and hitting new ones in and all that shit. It was like ‘who cares’. Plus, once we started to hang out together as friends again we realised we should create something new, not try and rebuild the old stuff. It’s all about the future once again. I hate to keep hammering that point, but for me, modern electronica should always be moving music forward. The thought of spending a year recreating our old live set was just awful.

THREE CHAPTERS – ONE SONG

But forget all that, let me play you some of the album. The first track I’m gonna play you is Other Planets. The story behind this is that we’ve been working on this project for a year or so. We were using Andy’s philosophy of ‘let’s spend 45 minutes on this, and when that magic moment happens, save it and move on’ – rather than my usual regime of, ‘I’m gonna spend six hours on this – therefore it will be better’.

So, Part A of the story behind this track is that every week we’d get together but not discuss how we were going to work or what we were going to do. We’d go to the pub, then come to the studio and have a few ideas ready to go. This particular night I closed both doors to the studio so Andy couldn’t hear what I was doing, and got this Eno-esque soundscape thing happening. Then I muted everything, told Andy the track was in B Minor and asked him to do his thing. Initially it sounded kind of ordinary, but we listened to it after a break and then Andy decided he’d play a new bass line. Now Andy – who isn’t a great player – is fumbling around on it, and then just quantises it into something I would never have come up with – and it sounds amazing!

AR: I pretty much rely on quantisation and accidents!

PM: He does… but instead of hearing 16th-notes, I was hearing triplets. So then I quantised it to 12/8 instead of 4/4. I reckon this was possibly the quintessential moment of the album. We both listened back and went, “Quantised 12/8 triplets. Whoah!” For me a cardinal rule is you never do triplets; it’s so Gary Glitter. But this really worked and went on to become the funkiest bassline on the album.

Part B of the story actually began five years ago while touring through Europe with The Dissociatives. We’re in Paris and this kid comes up to me and asks if he can show me around Paris. We can’t speak French, we’ve got no idea where to go, so we agree to hang out. Then we end up having this awesomely crazy night in Paris with him.

Part C of the story then goes something like this: last year I’m in New York, and I go and see The Field and Juan MacLean. I go outside for a cigarette and this kid comes up to me and says, “Remember me?” I’m like, “Yeah… Paris right?” So we ended up hanging out and becoming good friends. On the final night I’m in New York and I end up back at his apartment in Brooklyn watching the sunset come up over Manhattan, just hanging out with him and his girlfriend. He’s a rapper and he plays me some of his music. I pretty much hate white rap, but I really loved his stuff. So when I’m back in Sydney, we send it to our friend in New York and he sends back four rapping vocal tracks: three were great, but one was amazing. Freddy the rapper came through!

BW: The track certainly carries some attitude gentlemen, and it’s most definitely ‘forward’… very progressive indeed. Have a listen to Other Planets (featuring MDNA) via the AudioTechnology website: www.audiotechnology.com

At that point I had the bass and drums covered, so it was like, ‘sorry band, I’m taking over’. Suddenly there was no need for a drummer. You know that guy that’s always annoying you to get his reggae track into the set? – Paul Mac.

BACK TRACK

AR: But to get back to the track’s inception. I find it’s often more creative to limit yourself in a different way each time you start a track. For example, what would it be like if one of us wrote a bass line not knowing what the other person had done, or what would it be like if we tied one hand behind our back, etc.

BW: It’s almost a way of tricking yourself into doing something more instinctive, fooling yourself not to use your usual arsenal of playing skills.

AR: I agree with that, I definitely agree with that.

BW: So who came up with the ‘other planets’ lyric?

AR: Ahh, the lyric isn’t mine. I stole it. This story always sounds so pretentious, but I did, so I may as well mention where it came from. I ‘repurposed’ it from a poem by a 19th Century poet called Stefan George. The poem was later appropriated by Arnold Schoenberg for a piece called Ach du Lieber Augustin, but it was the line itself that really stuck with me. I steal shit like that, and that particular gem I really wanted to steal. I think the original prose is; ‘I feel the wind of other planets’, or something like that, so I’ve melded it to suit my own perceptions. I knew I wanted to use the line someday, and when Paul did his Eno thing I knew that was the moment. It’s the most progressive thing we’ve done I think. That triplet thing was like splitting the atom for me. I’d never have thought of a groove like that in a million years!

BW: What did you think of when the lyrics turned up?

PM: Our jaws just hit the floor, we loved it. You’ve really gotta grab those moments, and make sure circumstances allow them to happen.

RESPONSES