Many Hands Make Light Work

When Gang of Youths keyboardist Jung had just weeks left on his visa, the whole band decided to up and move to London with him. But there was the small matter of recording an album first. This is the story of how a talented team turned a last-minute session into the ARIA-winning album, Go Farther In Lightness.

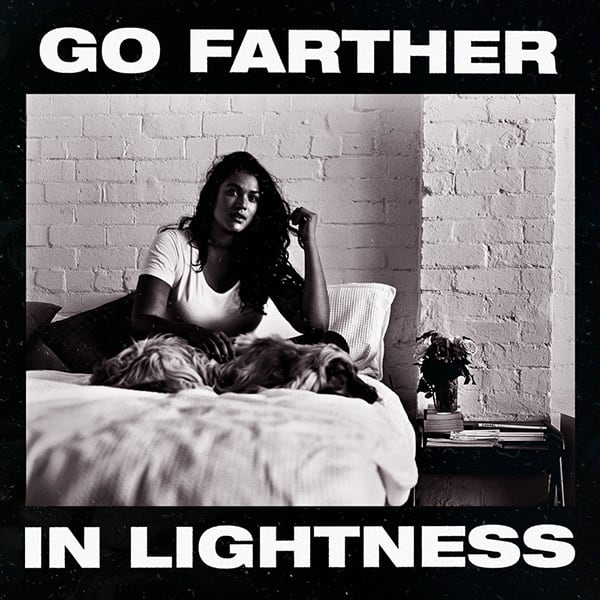

Artist: Gang of Youths

Album: Go Farther In Lightness

Adrian Breakspear Portraits: Oscar Colman

The whole reason guitarist Joji Malani joined Gang of Youths was because singer Dave Le’aupepe came to him with a noble cause; to make an album, The Positions, as a monument to his then fiancé who was losing her life to cancer. “It seemed worth leaving aside other aspirations in order to pursue that,” recalled Malani. Things got complicated, and Dave credits his bandmates with helping him through the breakdown of his marriage and struggles with substance abuse. What most people don’t know is it goes both ways, said Malani, that Dave saved him too. “Being a Pacific Islander, I had other ambitions,” explained the once budding sportsman. “There was no guarantee I was going anywhere, but that was the intention. I also came from a really academic family and music wasn’t really seen as something to pursue. Then I had a life-defining injury to my knee; I pretty much couldn’t walk for two years. Dave was one of the few people that would come and visit me every day. As much as Dave says we saved him, he did the same for us; me especially.”

VISA-VIS WITH DESTINY

Trials seem to be a catalyst for the band’s album-making schedule. This time, their American keyboardist Jung was having visa issues and had to leave the country in a matter of weeks. Initially, they’d planned to head over to producer/engineer Peter Katis’ studio in Connecticut. He’d mixed The Positions and has a long history with bands like Interpol and The National. His bass and drum sounds were two big reasons Malani was interested in working more closely with him (“maybe it’s a black thing”), but it just seemed like too much pressure to move to the US. “We’d always intended to move overseas,” he explained. “But America’s a hard place to live right now, whereas London seemed right.”

With less than a month to pull the session together they turned to Adrian Breakspear, a Brit engineer who followed his Aussie wife south. He’s since become the lead engineer at Sony Music’s in-house studio, and he, too, had worked on The Positions as well as the follow up EP, Let Me Be Clear, and now the 2017 ARIA Album of the Year, Go Farther In Lightness. It was an easy decision for the band to go with Breakspear. “Obviously an engineer has to be adequate at their job,” said Malani. “However, the most important thing is they’ve got to not just know the people in the band, but have a really good understanding of each person. Adrian definitely has that. He really knows how we all work and how to get the best out of all of us.”

Breakspear is the perfect match for the band’s ambitious compositions, especially considering the large proportion of strings on the album scored by Le’aupepe. In the UK, Breakspear learnt over the shoulders of engineers like Mike Crossey (Arctic Monkeys, Foals), Mike Hedges (The Cure, Siouxsie & the Banshees), Chris Sheldon (who mixed The Colour & The Shape) and Marcus Dravs while working on Coldplay’s Viva La Vida. He became a pinch hitter, recording string sections, pianos, or anything acoustic that was troubling producers and engineers who primarily worked in the pop world. Breakspear’s prowess with his toolset hasn’t gone unnoticed, earning him a nominations for ARIA Engineer of the Year in 2015 and 2017.

SONY STUDIOS

The record was tracked at Sony Music’s studio in Sydney, where Breakspear is able to isolate bands without too many compromises. It allowed the band to work on tracks any way they pleased; sometimes tracking live takes, other times laying parts over existing demos, or just Le’aupepe and a piano. It suited Malani’s state of mind, who was in a bad relationship and wasn’t feeling inspired. “I was in a really weird place in life,” he said, deciding to sit back a little more and let others lead the way. “Instead of my first instinct being to go to the guitar or another instrument, I wanted to see what Dave, Jung or any of the other guys would do, even on guitar. There were four songs I didn’t play anything on.”

The studio has plenty of top-notch vintage gear — three Blue Stripe 1176s, two UA 175s, an LA2A, two original Pultecs — mixed with newer pieces like Avedis MA5 preamps, Distressors and Al Smart gear. There’s a Yamaha C7 grand piano, which featured heavily on the record, and the mic collection includes a pair of Neumann U67s and a vintage U87, which paired neatly with Breakspear’s own Wagner U47 clone. (He’d managed to pick up a barely used Wagner over a year ago, and it’s become his go-to vocal mic ever since. The majority of the vocals on Go Farther In Lightness were recorded with Wagner, the rest with a Shure SM7 to let Le’aupepe loose around the studio.)

VOCAL CORNERSTONE

Dave Le’aupepe’s vocals are the cornerstone of Gang of Youths. They can range from lamenting and menacing, to triumphant and passionate, and both Breakspear and mix engineer, Katis, were intent on featuring every last nuance. “There’s a clip on YouTube of a young Dave playing Overpass, just a guy playing a song on guitar in a bedroom,” said Breakspear. “You can hear the sound of his voice even back then. I thought we should put a moment like that on the album, where it’s just a bit roomy and lo-fi, and you don’t have to be posh about it. That’s where the Go Farther In Lightness interlude came from. It wasn’t even real piano, it was a Spitfire Audio sampled piano overlaid with street noise ambience. I mixed it, but Dave said, ‘turn the ambience up way louder, they’re not going to be listening to me, it’s more about the world.’”

But people are listening… to every syllable, so engaging is his performance. For most of the album, his powerful, deep baritone is single tracked — a “pretty, impressive, bold move,” reckons Katis. At times it was subtly supported with unique arrangements and effects like adding an octave-down double on Do Not Let Your Spirit Wane, and a “Leonard Cohen mumble” underneath Persevere, as well as a vocoder-element using Antares’ Harmony Engine, “with all the nastiness taken out,” said Breakspear. Katis even got in on the act, occasionally “sneaking in a little Soundtoys Alterboy to subtly add harmonic complexity with an octave up and down.”

“If I’m given a bunch of vocal doubles and harmony parts I’ll leave the main vocal dry and put really trippy effects on the backing vocals; like a tremolo, tape delays and modulation. It helps the lead vocal stand out because if you put a deep tremolo on something it makes it quieter. It gets them out of the way without literally pulling them down.”

Breakspear is addicted to details and spends a lot of time cleaning up vocals and evening things out so they don’t hit the compressor too hard. Katis on the other hand recently had someone point out they’d “never seen anyone use less automation on a vocal,” he recalled. “I don’t think it’s because I’m lazy. I feel like I should be able to find the right level, the right sound, the right amount of effects and compression. And those setting should be right for the whole song. Many times that’s not the case, but a lot of times it is.”

Breakspear’s prep likely helped in this instance, but Katis will do some automation. “I’ll set a fairly good level and then clip gain down the level of the verses as opposed to automating. That way it hits the compressor a little more lightly, almost like you’re singing more quietly.” If the vocal was ever overwhelmed, Katis would drop the level of the music, not turn up the vocal. Everything about the song would revolve around the vocal.

DE-ESSER DANCE

Of course, there are other tools to keep vocal levels consistent. “I use a combination of compression, mostly for the sake of reducing dynamic range,” said Katis. “Then the fun part is using compressors that add colour. However, it’s always the compressors that make it sound exciting that also make high-end really problematic.”

Katis hates an overly bright vocal, “but for me to push the vocal to a point that’s sonically exciting and energises the performance, sibilance becomes such an issue.” Rolling off the high end produces an unsatisfying result, so Katis solves this problem by doing “a crazy de-esser dance with multiple de-essers all doing different things. There’s no magical de-esser that will fix all your problems, though I’ve been trying a new plug-in called Soothe, which is really powerful, and I love the Fabfilter de-esser. I’ll typically use really boring ones like the Waves Renaissance De-esser at the top of the chain narrowly addressing 6kHz or the frequency that’s really killing you. I take out a bunch. Then there’s usually some overdrive or an 1176-style compressor, which I’m a big fan of with all buttons in, but they definitely make things crispier. Then I’ll use the same plug-in again after the compressors, but instead of having it at 6kHz, I might have it at 4kHz. Then I’ll have it again at 2kHz, which is not really de-essing, it’s just managing the peaky midrange. At the very end of the chain I’ll use the really cheap one that comes with Pro Tools. I don’t like it, but if you set it at the lowest amount, like 0.1, and a frequency of 16kHz, it will still slam it. It’s like a catch-all, if it’s still getting hit pretty hard at the end of your chain, your vocal is still too bright.”

SUM OF A DRUM

As Malani mentioned, drums were a big reason for going with Katis, and his pounding, signature toms and densely-packed snare punch are on display throughout the album. However, Katis said whenever he’d really push the drum sounds, the general feedback would be to tone it back down. “They didn’t want me to reinvent the sound they’d recorded,” he said. “Every time I mixed a heavier kick drum or fatter snare, they really just wanted it the way it was. It makes sense because it left room for the arrangement. If he was hitting the drums on the 1 and the 3, then you’ve got plenty of room, but this is pretty busy rock stuff.”

Breakspear’s drum mic setup was relatively straightforward, with Coles 4038 ribbon overheads measured out from the snare, a combination of the newer AKG D12VR inside kick with a scooped setting, and a Neumann FET47 outside. He prefers an Audix i5 dynamic mic on snare top with either a Shure SM57 on bottom, or a condenser like an AKG C414 if it’s a quieter song. He puts Sennheiser MD421s on toms, and sets up a crush mic over the kick shell rim. Because the Sony Studio’s live room doesn’t have vaulted ceilings, Breakspear prefers to capture a close ambience. He measures out double the distance of the overheads to the snare, and places his Wagner U47 there to avoid any phase issues, adding “a sense of body without slap or being a big splashy room.”

From there, it went to Katis, who made a few surprising remarks about his mix. Firstly, “I’ve almost never in my life compressed a snare drum.” Which seems counterintuitive to what you’re hearing. He also swears he rarely ever uses anything besides subtractive EQ, expect for some high-end boosts. Despite the deep-sounding tones, he’s almost always cutting down low. Instead, much of his tone comes from employing an elaborate bus system and analogue summing chain. He can treat the drum bus quite aggressively. “I’ll normally use more compression or distortion to bring out the brightness of it, then clean up the low end with EQ,” he explained. “I’ll try all different things on my drum bus, which is the joy of mixing now with computers and plug-ins. It will definitely change song to song.” A favourite is the UAD Studer A800 plug-in, playing with tape speed and biases to accentuate high end, staying wary of any excessive low end. He at one time used SSL-style bus compression, but finds it “too plasticky and toppy sounding.” He’ll try things like UAD’s Fatso, or Chandler Zener Limiter, which is “usually a mistake but sometimes it’s genius. A lot of plug-ins that add instant energy and make stuff pump, were just too messy. On that record, almost every time I’d take the aggressive treatment off the drum bus and just push up the overhead, let a bit more high end in and let it fly a lot more naturally.”

Katis’ snares always have a lot of body, but his main challenge is the same as everyone else’s. “Since the beginning of time, the trick has been to get the snare bright enough without the hi-hat being annoying,” he said. He’ll try gating it, but “when the drumming’s not straightforward or there’s a lot of ghost notes, the gating just doesn’t work.”

He also doesn’t trust gates on toms, preferring to manually clean them up. “In the old days when you were on tape, it was a real art form to get the leakage to sound musical,” said Katis. “On occasion I will still do that if I accidentally leave them on for a while and get used to it, but in general I find that if the toms are clean you can really dial in the attack and the bottom, the level and the effects, and make them sound better.” He’s also not afraid of taking the low end out of toms, because he typically finds there’s way too much once they’re souped up. He also peak limits them to avoid a stray hit coming through 8dB louder. “It’s an intuitive dance,” he explained. “Then whatever ends up sounding good I should probably turn them down 4 or 5dB.”

Katis tends not to parallel compress the drums these days, preferring to take Breakspear’s close ambient mic or crush mic feed and go to town on that, making it pump. He’s not afraid of using samples to add tight low end to a kick drum, but tries to avoid it. “Otherwise all your records can start sounding the same if you’re using the same samples,” he explained. “It’s definitely better if I can get the same tone with just the natural mics.”

The entire time Katis is mixing, the stems are all getting processed through his elaborate summing setup. He was a self-confessed gear freak for so many years, that when he moved to mixing in the box he still had a lot of mix bus quality stereo compressors: “I can’t use them all on the mix bus so I have them on my stems.”

“I come out of really nice Burl converters into a Thermionic Culture Fat Bustard analogue summing mixer,” began Katis. “Once you get to a certain range of decent quality analogue summing mixers, they all sound really good, but there’s something about this one that really stands out to me. Then I have an API 2500 on the drum bus, a super expensive EAR 660 on the bass bus. Is it important? I don’t know, I have it. I know for a fact it’s adding colour. I have a Neve 33609 on the keyboard bus, and a Pendulum Audio 6386 on the guitar bus. It’s named after the tube in it, the same as the Fairchild tube.”

All the compressors are preset so he can recall any mix and not have to tweak a knob. Similar to the way the Pro Tools de-esser provides a watermark for vocal brightness, the bus compressors judge whether the mix is too hot. “They’re all set so that when whatever hits it is really cranking; it’s just tickling the compressor,” said Katis.

When it comes out of the summing mixer, the stereo mix goes into a Thermionic Culture Phoenix vari-mu compressor, then into a Dramastic Audio Obsidian SSL-style compressor. From there it travels to a Studer A820 1/2-inch tape machine which he’ll sometimes print to, then through a Pendulum Audio analogue peak limiter. “Again, it’s all doing very little, but going through all those tubes and transformers does do something,” said Katis. “Take them away from me tomorrow and I would find a way around that. Everyone pretended the volume wars were going away, but they’re back and worse than they’ve ever been in the history of music. People are so obsessed with the volume of the record. After it hits the AD conversion back into Pro Tools — before it hits the stereo print track — I have an aux mix where I can put some additional treatment. I will add more gain, a little compression and tape saturation, and a little bit of EQ to clean things up. I will also add a bit of peak limiting that gets cemented into the final mix, but not a lot. It lets me run that whole analogue summing chain at an appropriate level. By adding the gain digitally, it allows me to run all the analogue levels more old school and have it sound better — less choked. Then everything I give to the band is 5dB louder than I give to the mastering engineer.”

Katis doesn’t miss mixing on a console anymore: “I mean how do you mix a song for a band in Australia from the east coast of the US without recall?” In the end, the band was able to record in Sydney, and move to London while the record was mixed in the US. To make light work of the situation, their team of engineers, Breakspear and Katis were “as determined as the band to make a record that everyone’s really psyched about,” said Katis. “People were either going to be pissed off about this record or really impressed. I’m just really happy that it’s the latter.”

RESPONSES