Review: RØDE TF-5

Three years ago, word got out that Røde was working on a new range of high-end microphones designed in conjunction with classical recording engineer Tony Faulkner. The TF-5 matched pair is the first commercial offering. Was it worth the wait?

In January 2016 I was at the Sydney Opera House watching Grammy Award-winning engineer Tony Faulkner setting up to record a live performance of Beethoven’s 9th Symphony. All the microphones were Rødes, and among the collection were some prototypes that included a pair of small single-diaphragm condensers. They were hanging above the stage by the time I got there, so I couldn’t get a close look. Tony referred to them as his “thinking man’s reverb” mics and said, “They look remarkably like NT5s with omni capsules, but these are revised capsules and electronics and they’ve got a flat black finish”. You can find that quote in my interview with Tony [‘Stereo Masterclass’, Issue 115 of AudioTechnology], along with further discussion of the work he’d been doing with Røde to develop new microphones.

Three and a half years later, after much speculation online and off, Røde presents the TF-5: a small single-diaphragm cardioid condenser mic with a flat black finish, sold in matched pairs. Gone is the traditional ‘NT’ prefix, replaced by Tony Faulkner’s initials. Could the TF-5 be a cardioid version of the mics I saw hanging above the stage at the Sydney Opera House?

SURPRISINGLY LARGE, SURPRISINGLY SMALL

The TF-5 matched pair’s packaging is surprisingly large for something containing two small condenser microphones. Sliding off the outer sleeve reveals a box made of stiff card, about 3mm thick, with a black finish. It’s not polished wood and it’s not injection-moulded plastic, but it’s good enough to ship its contents safely around the world and therefore it’s good enough to carry them to your next gig. Give it a layer of gaffer tape and it will probably last a lifetime.

The TF-5 itself is surprisingly smaller and heavier than expected, measuring 99mm long and 20mm diameter, and weighing a satisfying 114g — it would be easier to believe you’re holding a solid metal rod rather than a microphone. In comparison, Neumann’s KM184 is bigger all around at 107mm long and 22mm diameter, but considerably lighter at 80g.

The box seemed unnecessarily large until I noticed the fabric tabs at the sides. Pulling them upwards lifted out the upper tray holding the mics and clips, revealing a lower tray with a pair of foam wind filters, and, happily, Røde’s Stereo Bar. The inclusion of the Stereo Bar means the TF-5 matched pair is a complete ‘stereo-miking-with-cardioids’ package, BYO stand and cables. There’s also a small hardcover booklet with full-colour pics, specs and background information about the TF-5.

SPECIFICALLY SPEAKING

The TF-5’s association with Tony Faulkner makes it clear that it’s intended for recording acoustic music. It can be used in a stereo pair to capture an entire ensemble, as a spot-mic on an individual instrument within an ensemble, or as a close mic in the studio. Browse through any on-line forum for people who specialise in recording acoustic music and you’ll find that the most revered mics are typically small single-diaphragm condensers from Schoeps, DPA, Sennheiser and Neumann. Two things that most of these revered mics have in common are relatively flat frequency responses and consistent polar responses across a range of frequencies.

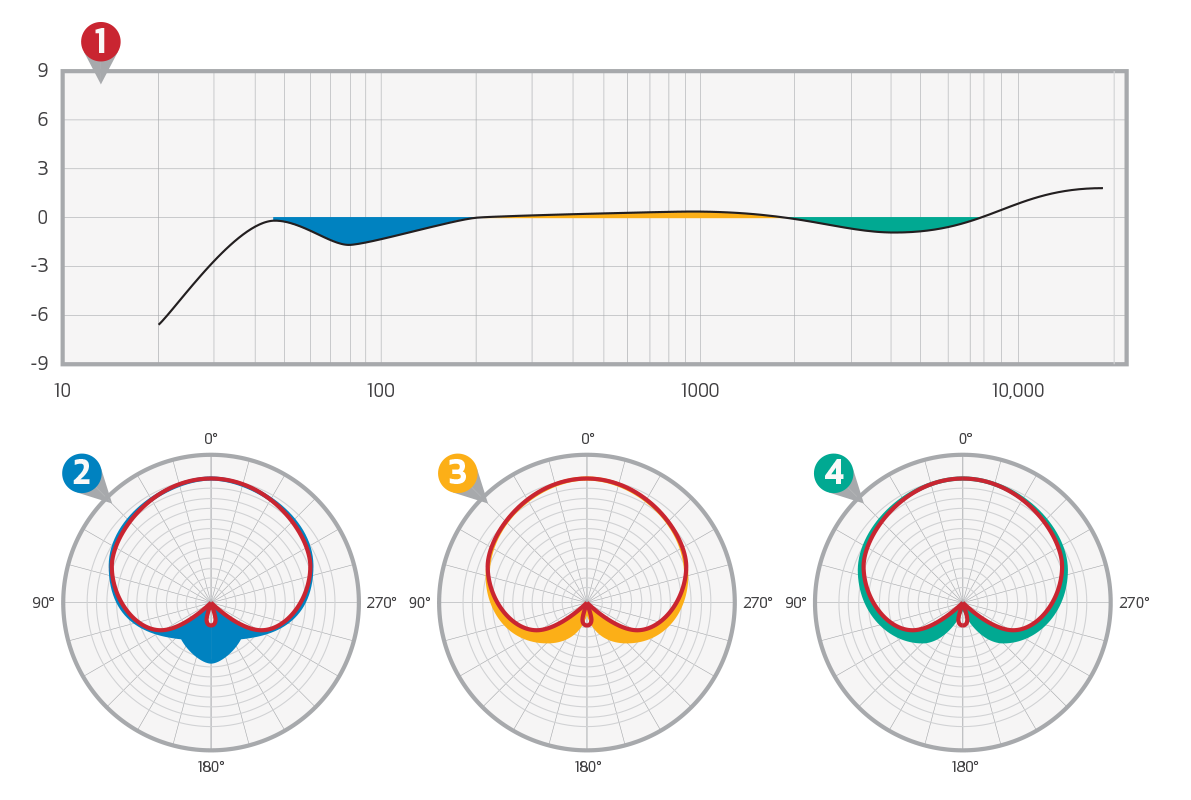

Microphones that exhibit these qualities are generally referred to as being ‘accurate’. Throughout the TF-5’s promotional materials, Røde have downplayed the term ‘accurate’ in favour of ‘natural’. I’m guessing that’s because the TF-5 does not objectively qualify as ‘accurate’; it does not have a flat frequency response, and it does not have consistent polar responses across a range of frequencies. On paper, at least, the much older NT5 outperforms it in those respects. After using the TF-5 and being puzzled by how the resulting sound was much better than its frequency response and polar responses suggested, I wondered if there was more to those deviations than meets the eye. Or ear.

NEED TO KNOW

RØDE TF-5

Matched Pair Cardioid Condenser Microphones

There’s not enough room in this review to go into it with detail, but here’s what I’ve noticed. The dips in the frequency response correspond with areas in the polar response that get wider than they’re supposed to, and the peaks in the frequency response correspond with areas of the polar response that get narrower than they’re supposed to. Also, the size of those peaks and dips in the frequency response are roughly proportional to the size of their corresponding deviations in the polar responses.

Assuming the TF-5’s published frequency response was measured at 30cm and can therefore be considered an on-axis measurement made under anechoic conditions, it would be easy to believe that the unusual dip at 80Hz (which starts at 45Hz and ends at 150Hz) was engineered into the TF-5 to balance the effect of the additional low frequency energy entering from behind, as shown in the 125Hz polar response. This would allow plenty of low frequency energy/reverberation (stuff that audiophiles refer to as ‘bloom’) to enter the rear of the microphone without making it bass-heavy. Meanwhile, the subtle boost at 1kHz works with the slightly narrower-than-cardioid directionality shown in the 1kHz polar response, compensating for the lower sensitivity from the sides at 1kHz by adding a touch more emphasis on-axis. Finally, the upper midrange dip from 4kHz to 5kHz works in conjunction with the wider directionality shown at the rear of the 4kHz polar response to tame on-axis performance noises (bow noise, fret sounds, etc.) while also giving off-axis reverberation a small boost in clarity.

Could the combined effect of these deviations result in a microphone that is subjectively more ‘accurate’ than it measures, and therefore sounds ‘natural’? I suspect that measuring the TF-5’s frequency response in a reverberant environment, where sound energy can arrive at the microphone from all directions with equal probability, would yield a much flatter result.

OTHER SPECS

The TF-5’s self-noise of 14dBA puts it right in the ballpark of similar mics from Neumann, DPA, Schoeps and Sennheiser. Its 68Ω output impedance should be fine for driving long cable runs, while its relatively high 7mA current requirement remains within the 10mA maximum specified for phantom power.

The maximum SPL of 135dB for 1% THD alongside its high sensitivity of 35mV/Pa make it clear that the TF-5 is intended for use with acoustic instruments and/or distant miking. I wouldn’t be rushing to put one inside a kick drum or facing into the bell of a trumpet, but I’d have no hesitation using one to spot mic any instrument in an orchestral recording that was soft enough to require spotting, or use a pair to record a big symphonic piece from anywhere above and behind the conductor.

IN USE

I tested the TF-5s on everything from drum kits, acoustic guitars and grand pianos to bamboo flutes and singing bowls. Those recordings formed the motivation behind my earlier speculation about the symbiosis between the TF-5’s frequency response and polar responses. Whether intentional or not, it’s very effective. Among other things, it creates a microphone that is fast and easy to use when recording acoustic instruments and ensembles.

ACOUSTIC GUITAR

I made some comparison recordings using acoustic guitars in a recording studio, choosing two mics as reference points: Neumann’s similarly priced KM184, and DPA’s considerably more expensive 4011. Between them I aimed to create a set of comparisons that allowed the listener to determine where the TF-5 sat on the price/performance scale. You can read about those comparison recordings in this issue’s Last Word, or scroll down to ‘Hear For Yourself’ to listen to them.

There are times when any one of the three mics could be the preference, depending on the strings, the type of playing and what the recording was destined for. For close-miking applications where the acoustic guitar is intended to feature in a complex multitrack recording, most engineers accustomed to working in popular music or rock would prefer the edgier sound of the KM184 in the belief that it would cut through the mix better. For applications where the guitar was a background textural element or a more natural sound was required, the mellower tones of the TF-5 would be the preference.

Things get more black and white against the 4011. There are times when it is an obvious preference over the TF-5, and times when it brings out too much of the performance noises such as plectrums and ‘zinging’ metallic string resonances that are hard to fix with EQ. In those cases the TF-5 gives a much more ready-to-use sound.

It’s important to note that throughout these comparisons the TF-5 is never out of the game, whether rubbing shoulders with the similarly priced KM184 or punching above its weight against the more expensive 4011. Whenever the TF-5 comes out second best, it’s a close second – and that’s against two mics that have been used for recording acoustic guitar for decades and have therefore helped to define our ideas of what an acoustic guitar recording is supposed to sound like.

DRUM OVERHEAD

With a few minutes left at the end of the guitar session we quickly put up the TF-5 and the comparison microphones in a drum overhead position about a metre above the the crash cymbal and hi-hats, primarily to test it on cymbals. The TF-5 was clearly preferable here, with cleaner cymbals plus stronger and more extended low frequencies – a finding that seemed at odds with the published frequency response and its -1.5dB dip at 80Hz, adding credence to my earlier speculation. The in-house engineer described it as sounding as if he’d put parallel compression on the TF-5 but not on the others. I agreed with his observations; the TF-5 delivered a richer and more solid bottom end. Also, although the 4011 and the KM184 were in the same position as the TF-5, both sounded roomier; particularly on the kick drum. The preference for the TF-5 here was a no-brainer.

They sound good enough to be considered ‘special’, but are priced low enough to be considered ‘work horses’

UNCANNY KNACK

The TF-5 has an uncanny knack for capturing more of the sounds you want to hear and less of the sounds you don’t. The best examples of this were the recordings of the singing bowls and the bansuri (transverse bamboo flute). Singing bowls have a relatively low output with very little high frequency content to mask the sound of the rod rubbing around the edges to get them resonating. The bansuri has a similar problem, but with blowing sounds. I’ve recorded both instruments before and, given a choice, I’d never use a small single-diaphragm condenser for these applications, preferring the lower self-noise and mellower upper midrange of a large dual-diaphragm.

The performance spaces were average-sized rooms in a house with concrete/brick walls, polished tiled floors and lots of windows. From the moment I entered the room for the singing bowl recording I knew I was up for a challenge, so I switched to a ‘small room’ mentality: aiming to minimise early reflections while staying far enough back from the sound source to get something natural. A similar approach was used for recording the bansuri in an adjacent room. In both sessions it was surprisingly fast and easy to find the right microphone placement and, with the help of judiciously placed cushions to tame early reflections, some very good results were achieved.

The TF-5’s shallow dip in the upper midrange kept the performance noises at bay without requiring the mic to be moved too far off-axis from the point of excitation, while its relatively low self-noise meant that hiss wasn’t a problem — even against sounds that did not have much high frequency content to mask it. I found it easy to get recordings that had enough of the performance noises for articulation without becoming obtrusive. Nor are those performance noises ‘harsh’ or ‘etched’ — as often results from using small single-diaphragm condensers. Everyone agreed that the performance noises were in the correct perspective relative to the music.

GRAND PIANO

No review of a mic with the TF-5’s background would be complete without testing it on a grand piano. In previous mic reviews I’ve had access to well-maintained Steinways played by some of the world’s finest concert pianists in beautiful concert halls. No such opportunities came up during the review period for the TF-5s, but I’m sure other reviewers will get something out there. I was, however, very fortunate to meet an excellent concert pianist who owned a grand piano; a Yamaha G3 in a small room with about 1.5m of space on all sides. It wasn’t a Steinway and it wasn’t a concert hall, but it was a well-maintained piano in the hands of an excellent performer, and I’m always up for a recording challenge.

I aimed to capture a ‘direct but distant’ sound with minimal first order reflections and no strong attack transients from the hammers — the type of recording that, with a bit of reverberation, might sound like it was recorded from a further distance in a larger space. Taking the mics in hand and moving around the piano while monitoring in headphones, I quickly found a position that delivered the tonality I was after (albeit at the expense of a better stereo image), locked the mics into the Stereo Bar, and started recording.

I came away from that ‘small piano in small room’ scenario with some very acceptable recordings, made from two different locations around the piano. Despite being less than 2m away from the hammers in both cases, the attack transients were never hard or edgy, and there was very little on-axis ‘pinging’ from the highest notes. The low frequencies are warm and clear but not as pronounced as I was hoping for; I do not know how much of that was due to the size of the piano, the microphone placement, the inherent low frequency roll-off of cardioids at distances greater than 30cm, and the mics themselves. Nonetheless, the pianist was very impressed and commented that it made the piano sound much bigger than it was.

(See ‘Hear For Yourself’ to check out those recordings.)

LIVING IN STEREO

With the exception of the guitar comparisons discussed earlier, all the recordings mentioned here were made in stereo; all in difficult acoustic conditions and all with very little set up time, using near-coincident mic placements created on-the-spot by holding one TF-5 in each in hand while monitoring on headphones to find the best distance, height, spacing and angles before locking them in to the supplied Stereo Bar. All recordings turned out to be very acceptable, and I left a trail of happy musicians behind me.

I also found that I could go to quite wide angles between the TF-5s before sounds coming from the centre showed any significant changes in tonality. This is an often overlooked consideration when using directional microphones at wide subtended angles, whether in near-coincident or XY configurations. The popular ORTF technique, defined as two cardioids 17cm apart with a subtended angle of 110°, provides a good example. Typically placed a metre or so above and behind the conductor in an orchestral setting, the 110° subtended angle means the instruments to the far sides of the orchestra (violins left, cellos and basses right) are essentially on-axis to the microphones, while the instruments in the centre of the orchestra (violas and woodwinds) are arriving at up to 55° off-axis. If the microphones are duller to sounds arriving at 55° than they are to sounds arriving on-axis (due to inconsistent polar responses), the violas and woodwinds will be duller than the violins, cellos and basses — which is the last thing those instruments need, and usually leads to the addition of spot mics. I found no such problems with the TF-5s at subtended angles up to 120°, which is about the widest anyone is likely to use with a pair of cardioids.

For all the stereo recordings made during the review period I stuck with the included Stereo Bar, so that I was reviewing the TF-5s as a complete ‘stereo miking with cardioids’ package. The Stereo Bar allows a maximum distance of 20cm between microphone clips, which many would consider too short for a general purpose stereo bar, but it’s wide enough for all of the standard two-mic stereo techniques that use cardioids.

SPECIAL WORK HORSE

To my ears the TF-5 holds its own against mics costing twice its price, and the differences in the comparison recordings do not come down to an overall better or worse; rather, it’s mostly a choice between hyper-detailed or natural. Many times during the review process the TF-5 felt like an easygoing hybrid that offered the speed and precision of a small diaphragm with the smoother and mellower upper midrange of a large diaphragm, along with an occasional hint of ribbon roundness. It has a similar low midrange warmth as the Røde NT6/NT45-O combination, but the TF-5 has greater harmonic detail in that area, along with the directionality of a cardioid and its interesting symbiosis between the frequency response and polar responses.

I expect many studios will buy TF-5s as their main pair for drum overheads, acoustic guitars and so on. I also expect to see them in the microphone cupboards of many concert halls and performance venues, and wouldn’t be surprised to see a dedicated pair hanging from the ceiling as default recording mics. Finally, I would not be surprised if they became a popular choice with home studios and recording musicians because they make it quick and easy to get an acceptable sound, even on difficult instruments.

Are the TF-5s an evolved cardioid version of the mics I saw above the stage at the Sydney Opera House? I’ve no idea, but I can tell you this much: they’re a beautifully-engineered matched pair of microphones that were worth the wait. They sound good enough to be considered ‘special’, but are priced low enough to be considered ‘work horses’. You could probably put them in front of any acoustic instrument or ensemble and get an acceptable sound very quickly, and a great sound with a little more time. If you’re a working pro looking for more mics to expand your kit, or you’re ready to move up from project to pro, I honestly cannot see the point in looking beyond a pair of TF-5s – unless you’ve already got them.

In closing, I am reminded of a line from Tony Faulkner in one of the promotional videos, “Take them out of the box, stick two of them on a stand with the Stereo Bar, and enjoy how natural they sound.” That sums up my impression, too. It’s that easy.

HEAR FOR YOURSELF

During the course of this review I had the opportunity to make some comparison recordings that put the TF-5 against Neumann’s similarly priced KM184 and DPA’s considerably more expensive 4011. You can hear those recordings at the link below, and read about the process of making them in this issue’s Last Word. I will also try to include some of the other recordings that have been mentioned in this review, pending permission from the musicians.

Go to: www.soundcloud.com/audiotechnology

I am being commissioned to record a small village pipe organ and from what I have read it would seem that professionals tend to use Omni directional microphone pairs. If I use cardioid I might use my AKG C414’s or my Beyer MC 930’s but along came the Rode TF5’s and I have a dilemma.

Do I stick to the intended to be purchased Neumann KM 183 or go for these highly rated Rode TF5 ?

Any thoughts given the uses suggested go nowhere near the recording of pipe organs !

Just to clarify something at the start: you’ve said “small village pipe organ”. I’m not sure if you’re referring to a pipe organ installed a small village, or a small organ suitable for moving from village to village. The former could be a traditional pipe organ of the type that is permanently installed in a church or concert hall, while the latter could be a self-contained portative or chamber organ that is (relatively) easy to move from place to place. The approaches to recording each are quite different. I’m going to assume you mean the former: a pipe organ installed in a church or concert hall..

There are many ways to record pipe organs; it’s a topic that’s debated occasionally but at length in on-line forums. The most common approach, and recommendation, is to use a pair of small single diaphragm omnis. Why?

A pipe organ is an installed instrument in which the reverberation of the room is a major part of the sound. Due to this, and the distances that the mics must be placed in order to get the right balance of pipes and reverberation, it is important that the microphones capture the sound of the room accurately. That requires microphones with good off-axis response, which means small single-diaphragm condensers.

Another important part of the sound of a pipe organ is the low frequency response, which, combined with the need for distant miking, means the omni polar response is indicated. Any directional polar response will suffer from a lack of low frequency energy when used at the distances required for pipe organs (it’s all part of the ‘proximity effect’, as explained in the first instalment of my Microphones series, here: https://www.audiotechnology.com/tutorials/microphones-an-introduction).

Another important aspect of recording pipe organs, aesthetically at least, is to capture and recreate a sense of size and space. A large part of the impression of size and space in a direct-to-stereo recording is due to subtle low frequency phase differences between channels, which requires the use of spaced microphones (AB or near-coincident).

So, all things considered, a spaced pair of small single diaphragm omnis is your safest bet for recording organs.

However, you also have to consider the surroundings of the venue, and the aesthetic required for the recording. Although my default choice for recording pipe organs was always a pair of small single diaphragm omnis, I often got a more useable result from using other polar responses and adding reverb if necessary. For example, if it was a live performance with a noisy family audience (e.g. free Sunday afternoon concert in a local church, close to the street) I’d get a more useful result from a polar response that would allow me to reject the direct noise of the audience and/or passing vehicles, and make up for the lost low frequency energy with EQ: it’s easy to replace lost low frequency energy with a bit of EQ, but it’s hard to remove unwanted audience or traffic noise. (You can’t do much about reverberating audience and traffic noise, but it’s less of a problem compared to its direct sound.)

With those things in mind, the TF5s don’t give you any strategic advantage over your MC930s. Although I believe there’s a place in every microphone collection for a pair of TF5s, for the specific application you’ve described a pair of small single-diaphragm omnis such as the KM183s would be a safer investment. The TF5s would do a fine job in ORTF if you need a more controlled sound, but you can do ORTF with your MC930s.

It’s also worth noting that the KM183’s high frequency boost (+8dB @ 10kHz) can be advantageous in distant miking situations, compensating for the loss of high frequency detail in the air and making the mics sound closer than they actually are. If you get the distance and spacing right you should be able to capture plenty of the low frequency ‘bloom’ that characterises a great pipe organ recording along with a sense of the sound moving between the different sets/divisions of pipes – something I’ve heard organists refer to excitedly as ‘the dance of the pipes’.

And finally, it might be worth asking around on places such as the Remote Possibilities forum on Gearspace, or the Classical Music Recording Group on Facebook; there might even be someone there who will tell you how to make a great pipe organ recording using your 414s, your M930s, or a combination of both (e.g. ORTF with flanking omnis).