Name Behind The Name: Uli Behringer, Behringer Inc

In 20 years of turning audio manufacturing on its head Uli Behringer’s exhortation has been the same: “just listen.” Uli, we’re all ears.

The word ‘Behringer’ immediately polarises people. In equal measure it elicits smiles and frowns. In some cases the mention of the word prompts anger, finger waggling, fabulous tales, and statements that start with; ‘what you fail to understand…’ Few surnames have launched quite so many posts on audio forums: claims and counter claims; lives transformed and language that would make Courtney Love blush. Behringer Inc has just turned 20 and, according to popular opinion, in that time it’s been everything that’s wrong and right with audio.

But whether you’re a big fan or the most trenchant detractor, I think it’s fair to make the observation that Behringer has been resolutely beige – it’s relentlessly pressed into every aspect of audio without any obvious signs of passion or personality. You don’t buy Behringer for its flair or character; they’re items that get a job done at the right price.

Saying that, the formula has worked, you just need to take a look at the company’s trajectory as evidence – it’s been ballistic: from Uli’s garage, to a warehouse down the street, to a factory, to partnering with a Chinese operation, to owning and running his own factory with thousands of employees — Behringer City, no less — in mainland China. In 20 short years Behringer has become the most prolific and one of the most successful audio equipment operations the world has ever seen. But unlike the proverbial tornado in a junkyard magically forming a jumbo jet, the success hasn’t been some bizarre fluke, on the contrary, Uli Behringer has left little to chance. The journey has seen a lot of painstaking planning, calculated risks, business acumen and a genuine belief that he was changing the lives of struggling muso’s and engineers around the globe.

TUTTI FRUTTI

Central to the Behringer credo is affordability. But keeping prices low has meant Uli and his CEO Michael Deeb needed to keep a vice-like grip on costs and manufacturing. When I was invited to tour the Behringer factory in early 2007 I was struck by the focus on manufacturing ‘processes’, almost to the exclusion of everything else – the inference appeared to be: saving on a nut or a blob of solder here and there was more important than the sound.

It reinforced the notion that everything about Behringer was relentless and inevitable.

But enough’s enough, stung by this author’s accusation of his company lacking ‘soul’, Uli has turned his business “upside down”. The recent NAMM exhibition in the U.S. saw Uli jamming with muso’s, captivating journos, just generally being charismatic and cool… here’s a man on a mission: overhauling the Behringer image from beige to paisley; changing the flavour from vanilla to tutti frutti. Interesting times.

20 YEARS HARD LABOUR

CH: It’s been a remarkable 20 years Uli. You’ve come from maverick upstart to audio mogul in a short time. Do you feel vindicated?

UB: For the first few years many people didn’t understand what we were doing, or they didn’t think what we were doing was possible. And if people tell me I can’t do something then I’ll do my best to prove them wrong. That’s the maverick in me, then and now. But the first few years were tough – even banks didn’t believe in my plans.

CH: Right. So there’s a bank out there kicking itself right now!

UB: Yes, the Deutsche Bank. For many years as a student I was a customer of the Deutsche Bank and every week I would deposit the money I earned playing piano – a few hundred bucks every week. The manager always said, “Mr. Behringer, one day if you need credit, no problem, knock on our door.”

So anyway, the time came when I wanted to build new premises, so I put on my best Sunday suit, walked to the Deutsche Bank, knocked on the door and they said, “Mr. Behringer, as much as we’d like to accompany you on your way forward, we don’t believe in your idea.” And this was when I had a 100% security from my mother, the guarantor – so there was no risk on their part, they simply did not want to support me. I walked out almost in tears I was so disappointed. I wanted US$200,000 and they wouldn’t give it to me, so I found a little bank around the corner and the guy said, “Of course, we’ll do this.”

Luckily enough, we never really needed a credit line, we just reinvested our profit. I read the book by Mr Kakehashi, the founder of Roland, who I think is a most inspiring person. His book, ‘My Life for Music’, mentions similar early experiences: The products he chose were the ones he could turn over in three months. So he got a six-month credit line from suppliers, which allowed him to get the components, build the products, ship them, sell them and use the profits to pay the bills. That sharpened his instincts for exactly what the customer needed.

CH: What were those early days like?

UB: In those days we had five or six people on staff. We had a little lunch table where we sat together; there were no management issues or language barriers or time zones, we just discussed things and did it right away. Looking back, in many aspects they were crazy times, but fun times too. People were so motivated, trying to help, working late, sometimes weekends – nothing was too much of a bother. It’s something that we still have today, but we’re a bit more organized now…

CH: How did you make that transition from cottage industry to big industry?

UB: Everything starts with someone who ignites something. Ultimately you have to be passionate to do something and you have to find people who believe in you. You have to inspire people to say, ‘C’mon, we’ll do this together’. I think I’ve been able to convince a few people along the way.

CH: So what where you making and how were you making it?

UB: In the early days we produced de-noisers, which were perfectly suited to the eight-track machines of the day. Initially, we sold three a month, we ramped up production by 10 a week and I remember thinking, “We must be near saturation level”!

Now we’re producing 2.5 million products a year, and I think the sky’s the limit. But it was fun how we built that stuff. We had a metal shop around the corner which built the chassis, the PCBs came from another smaller factory, and we also bought a lot of surplus material from TV companies (Bosch, Siemens) – I would go to this warehouse, walk in and climb the shelves to try to find the stuff I wanted. I was able to buy a lot of components at a much lower cost that way.

CH:< So you were on a mission to cut costs from the beginning. Why was that?

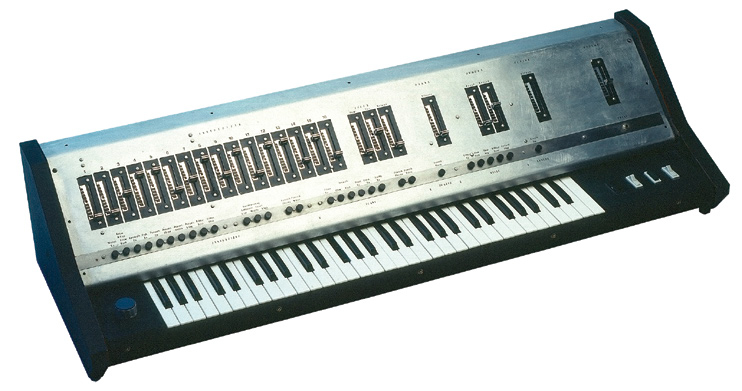

UB: When I moved from Switzerland to Germany in 1982 I studied classical piano and sound recording at the Robert Schumann Institute. But this school only had two microphones for 200 students. That was it. So you had to wait three months to borrow that gear even for a few hours. I had no chance of becoming a sound engineer in that environment! I needed equipment. I looked at what was available, opened the lid and thought, “Why does this cost $2000 when the components inside are worth just $100?”

Without considering the business implications I thought: I can make this stuff. And my friends said that if I was making one for myself to make one for them too. So I’d sold 10 pieces before I had actually built them! Then it was 50 pieces, and so on.

So it became apparent that a lot of people were in the same boat as myself – musicians simply couldn’t afford equipment.

He bankrolled this hopeless bunch of kids and gave us the keys to a very expensive, well-kitted out studio, and told us to go for it

MADE IN CHINA

CH: When did you realise your fortunes would be inevitably linked with China?

UB: In the early days I bought a lot of components from importers and distributors who bought stuff from China and I discovered that if you really want to pursue the dream to build great gear at a great price, Europe was the wrong place to do it. So as early as 1990 I hopped on a plane and went to China.

In China I soon discovered that these guys’ favourite saying is “No problem”. So if you believed them, you’d think they could do everything – I should have been more wary. So you’d get these wonderful samples, and then they’d send you a final shipment of ‘bananas’ – and I’m sure a lot of manufacturers who read this article will have gone through the same experience.

CH: So the factories and sub contractors had their own agendas?

UB: Yes. They’re trying to maximise profits too of course, so they can just as easily change priorities to other customers – they chase the money, so your supply-chain gets screwed up or, worse, they start to substitute your components with stuff you haven’t specified. You walk in and tell them how to do things and that approach only lasts for the time you’re there – you walk out of the factory and things go back to the old routine. You can’t control quality that way. And again, many people who manufacture in China will know exactly what I’m talking about.

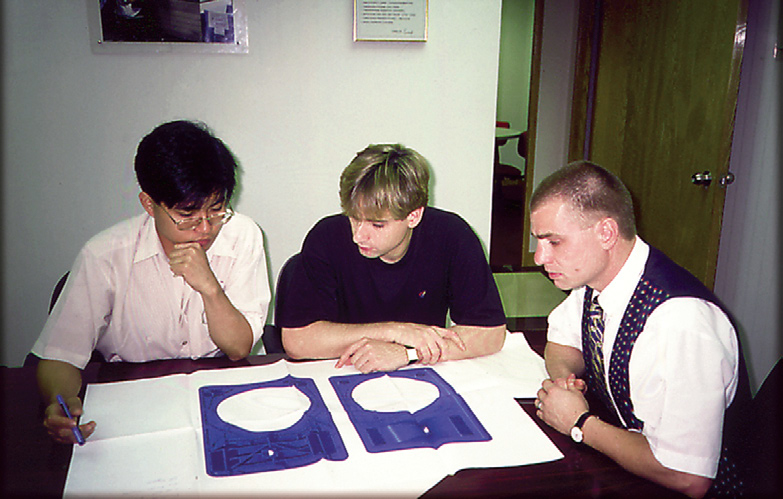

Ultimately, I figured out you can’t do business by fax, and back then email wasn’t what it is today. You had to be on site. So in 1997 I moved to Hong Kong. That was a real turning point. Up until then we were constantly struggling to get enough units built.

CH: Was it a case of running to catch up with demand?

UB: I was constantly using my cash to finance production again, and getting enough manufacturing equipment in and designing new gear for sale. In those days we didn’t plan for infrastructure properly; it was a case of putting fires out.

CH: And more recently you’ve taken a step further and actually established your own factory in China.

UB: That’s right, we’re one of the very few who have decided to go the hard way and build our own plant. That was about seven years ago now, and it was a very wise move. We’re now totally in control of our own destiny; it’s the only way we can provide the quality that you see today.

HOW LOW CAN YOU GO?

CH: Behringer led the low-cost charge but how low can prices go?

UB: For many years our mantra was ‘double the features, half the price’, but that hasn’t been the case for some time now. We don’t want to be the cheapest and we’re not the cheapest any more – we will never win that race. Our investment goes into quality and quality costs money. So we definitely go for added value.

‘Added value’ doesn’t necessarily mean more and more features; I think it’s more about refining the user interface. You want to make it super-intuitive for people to use, you want to automate a lot of functions and I think that’s the next direction. We work on convergence of technologies and invest heavily in R&D. We have R&D centres in China, the U.S. and Germany and employ about 160 R&D engineers – they’re the heart of our company.

CH: What makes you bounce out of bed in the morning?

UB: I enjoy working with great people. Having great people around me is phenomenal and I always appreciate having people around who are better than me. If you want to be successful in life you have to hire people who complement your weaknesses, and it’s worth remembering that there’s always someone better than you.

I admire a lot of people in our company and have a great urge to learn myself. I’m an avid reader, which helps me to learn from people better than me. You can’t afford to stop learning. My mum is 78 years old; she went back to university when she was 60, graduated at 65, watches CNN and calls me up to say; “Have you heard about the latest merger?” And that’s the stuff that keeps you young, that’s the trick to staying motivated. Again, you only need to look at [Roland’s] Mr Kakehashi. He’s over 80 and still involved in R&D. You gotta keep learning, that’s the fun in life – to improve yourself and give other people a chance to improve themselves.

POST SCRIPT: CHANGE FOR THE BETTER

So how exactly is Uli turning his company ‘upside down’? Uli reiterates the phrase ‘leaders not followers’ time and again; millions are being spent on R&D; and while others are laying off staff, Behringer is on a hiring spree. Will this amount to a raft of world-beating products? Only time will tell. But what is obvious from my interview with Uli is that we’re witnessing a generational change, and the New Behringer will look, feel and probably sound quite different.

RESPONSES