Mixing With Headphones 1

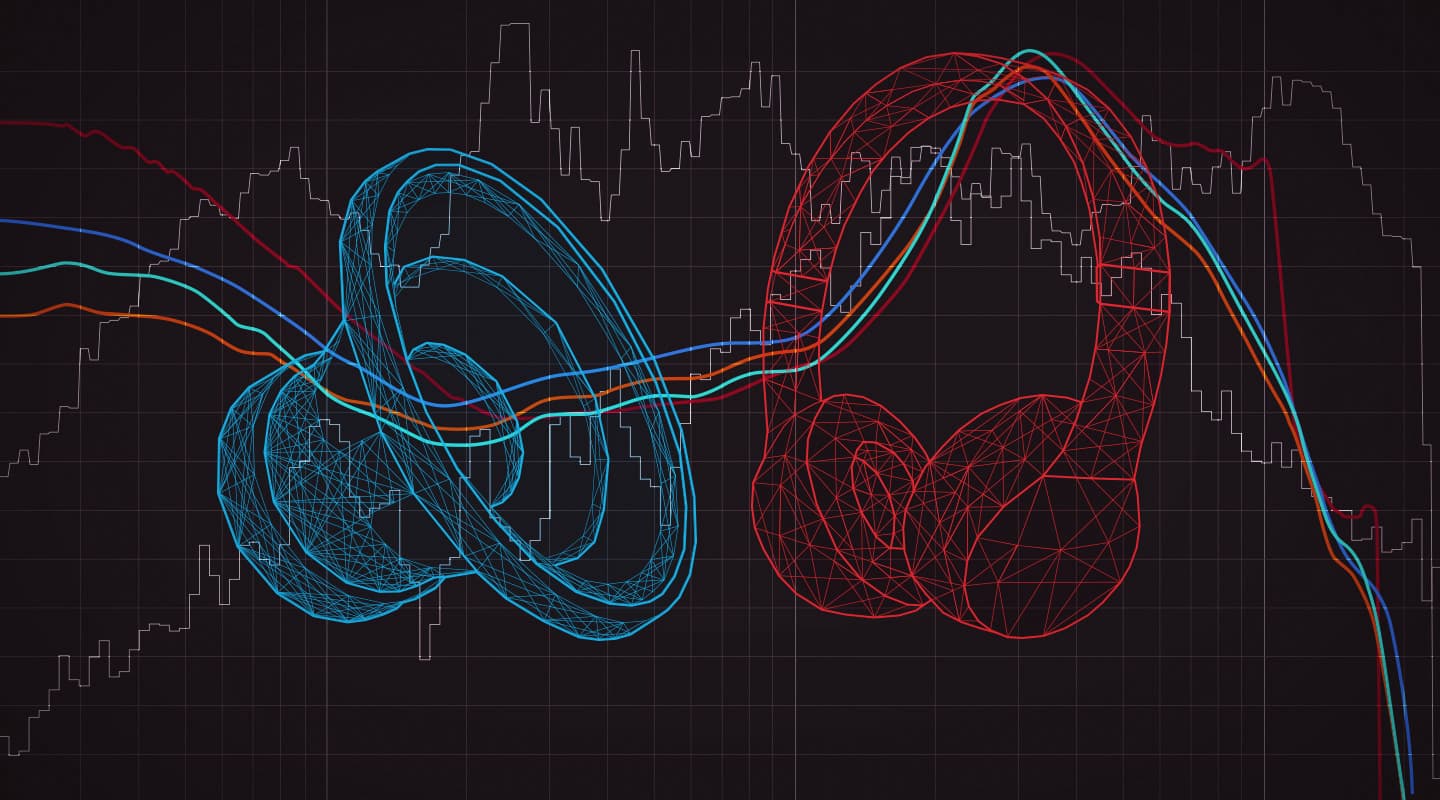

In the first instalment of this six-part series, Greg Simmons questions the relevance of large monitor speakers and argues that headphones are far more relevant to the majority of contemporary music consumers.

A dozen lifetimes ago – when sound was only as malleable as plastic tape – I spent my days working with resistors and capacitors, and my evenings playing with tape recorders and analogue synths. One of the technicians I was apprenticed to, a proto hi-fi buff aware of my sonic inclinations, handed me a cassette. “Listen in headphones, with your eyes closed.” That night I donned my Pioneer SE305s, pressed play and closed my eyes. A box of matches, shaken like a maraca, circled around me before passing over my head, under my chin, and stopping at the tip of my nose. I knew there wasn’t really a box of matches in front of me, but with my eyes closed this ‘advanced’ audio technology was indistinguishable from magic.

Eager to add this illusory effect to my electronic soundscapes, I soon learnt that it was a ‘binaural recording’ made with a ‘dummy head’: a life-sized model of a human head with a microphone mounted in each ear to capture the left and right channel signals specifically as they are heard by each ear. The illusion relied on two things. First, capturing the signal received by each ear along with its embedded Head Related Transfer Functions (HRTFs) – which are the changes imposed upon the sound as it passes across the face, around the head, and navigates the pinna (aka ‘ear flap’ or ‘auricle’) before entering the ear canal. Second, the signal from the left side microphone must go to the left ear only, and the signal from the right side microphone must go to the right ear only. The ear/brain system uses the differences between each ear’s HRTFs to determine the location of the sound, therefore keeping the two channels isolated is necessary for the binaural effect to work.

HRTFs vary from person to person depending on the size and shape of their head and their pinnae, meaning binaural recordings are more immersive to some people than others. The dummy head’s dimensions were averaged over a lot of different head and pinnae sizes and shapes, and captured left and right channel HRTFs with sufficient differences between them to fool most people – including me. However, playing the matchbox illusion through speakers was beyond disappointing. The illusion collapsed into the space in front of me, there were numerous instances of comb-filtering as the matchbox moved around within that collapsed space, and there were various imaging anomalies as the left and right channel signals and their HRTFs combined in the air – minimising the differences between them and confusing the ears rather than fooling them. In other words, the matchbox illusion only worked in headphones – they were the smoke and mirrors, and without them I could not ignore the man behind the curtain.

In those days nobody listened to headphones except audio pros, musicians in studios, Dads enjoying their stereograms without waking up the kids, and old men listening to race calls through mono earbuds jacked into pocket radios. Oh, and that weirdo standing in the train door fingering an air guitar while wearing one of those newfangled ‘Walkmans’ (a fad we all knew would never last), completely oblivious to the silent audience hiding behind walls of newspapers and magazines. Headphones were definitely not fashion accessories, and anyone wearing them in public looked ridiculous.

Disillusioned, I abandoned my plan of imposing artificial HRTFs onto my electronic soundscapes to create immersive binaural illusions. Those illusions only worked in headphones, and nobody listened in headphones…

A dozen lifetimes later and, thanks to the proof-of-concept provided by Sony’s Walkman and refined by Apple’s double-whammy iPod/iTunes combo, everybody is listening in headphones. Oh, except for that pencil-clutching weirdo in the train door immersed in the pages of one of those newfangled ‘journals’ (a diary by any other name is still a diary), device-less and oblivious to the rows of headphoned performers spot-lit by tiny screens while silently fingering air guitars, conducting orchestras with finger batons, striking out at knee drums and air cymbals, or navigating app-worlds that have artificial HRTFs imposed onto their electronic soundscapes to create immersive binaural illusions.

The cynical nostalgia evoked by the ‘nobody talks to anybody any more’ memes and tropes would have you believe that in the days before mobile devices, every train carriage, every bus and every waiting room was filled with strangers striking up genial conversations and filling the air with chatter. Atavistic nonsense! Before mobile devices people isolated themselves with newspapers, magazines and window seats, intentionally filling the air with the same lack of chatter as they do now. So slip on your headphones and forget about the negative-calorie small talk that Luddites cling to like Replicants embracing implanted memories – because it never really happened. Air boom, air tish…

In those days nobody listened to headphones…

Headphones have become fashionable, and therefore headphones have become status symbols. If I had a dollar for every time my Neumann NDH20s have been selfied by passers-by and diners at the night markets of South East Asia, I’d have enough to buy a Lamy clutch for every Yuccie arguing the difference between a journal and a diary.

Headphones have democratised high fidelity; for a few hundred dollars you can get a pair of high-status headphones that shrug “hold my beer” when pitted against thousands of dollars worth of speakers with their obligatory acoustic treatments and tightly-defined ‘sweet spots’. Headphones allow you to sit, stand, lay or move about wherever you like because you are the sweet spot; the room’s acoustics don’t even know you’re there.

Every major shopping mall has at least one store dedicated to mobile audiophilia and ‘head-fi’, i.e. high fidelity audio through headphones. If the stuff they sell seems expensive then you’d better re-assess your priorities because it’s chicken-feed compared to what it costs to get similar performance from speakers and their obligatory acoustic treatments, and you can take it with you anywhere.

Most significantly, headphones have supplanted speakers for the vast majority of music purchasing decisions and active music consumption (i.e. listening with intent rather than plastering sonic wallpaper over the background noise). Simultaneously, there has been a resurgence of interest in binaural recording and the immersive possibilities it offers without requiring a room full of speakers and the hope that the playback system adheres to the same format adopted during recording and mixing. Microphone manufacturers like Sennheiser and DPA have added binaural microphone systems to their product lines, and Neumann’s dummy head (aka ‘Fritz’) has reached new levels of celebrity. Popular music artists are now inserting binaural elements into their multitrack recordings, taking the headphone listener by surprise with sounds and voices appearing from beyond the musical soundstage.

As audio professionals, we would be foolish to underrate the significance of headphones in our mixing and monitoring decisions. Rather, we should be celebrating their popularity and exploiting their advantages. It is little wonder that many of the younger generation of producers are doing most of their mixing work on headphones, and consider the big monitor speakers as being primarily for show. However, the key word in that phrase is ‘most’. Speakers bear little relevance to their world or their market, but they’re still cross-referencing on speakers, and they’ve got mastering engineers downstream ironing out the kinks while listening through big monitor speakers.

What was once ridiculous is now mainstream. What is now ridiculous is placing too much significance on big monitor speakers and their obligatory acoustic treatments and inflexible sweet spots when mixing, because we’re living in a world where most people’s exposure to speaker reproduction is background music in cafés and shopping malls, platform announcements at train stations, and – topping the list – device notifications.

Ding!

I have hate mail…

Beautifully written and some very astute observations! Looking forward to the upcoming parts.

Well, I was prompted to recall an AT Editorial yester-milenia or at least yester decades about silibane and how it was heard everywhere in conversations, the writer of those early AT mags slips my memory; but his prayers are answered with the solitude of a smart phone, the chatter diminished. Anyway I realize that in the infomation highway that is Pro Audio, many like me have sucumbed to the Audeze or other for a reproduction that goes beyond a speakers we cannot afford and no longer belong as reference sets for verb tails and the like. But I do like where this series of yours is going and dont forget to take is over the edge of Atmos systems, can a headphone ever be used to replicate the speaker arrays?

The reproduction of Atmos in headphones is beyond the line I’m drawing for this series, Bart! It [Atmos in headphones] is not something I am very familiar with, which might become obvious in the rest of my reply but nonetheless let me explain my apathy-driven ignorance…

I am very cynical about surround/immersive formats in general (a surround format by any other name is still a surround format). I have seen numerous surround formats come and go in my life, and the recurring dynamic is: 1) studio owners invest huge sums of money in multiple speaker systems and room designs, and then work hard generating excitement about it to recoup and hopefully capitalise on their investment; 2) respected mixing engineers make endorsements saying they will never mix in stereo again, and 3) other companies start offering competing formats/standards. And what are the recurring outcomes?

For (1) it is the ‘Field Of Dreams’ effect (“If you build it, he will come”) except Shoeless Joe never sticks around, and the additional speakers are invariably removed or covered over because nothing says ‘loser’ louder than supporting a dead format. For (2) they invariably end up mixing in stereo again as the new surround format fails, because (3) competing formats always lead to ‘format fatigue’ where potential adopters siege it out to see which format will emerge as the standard and, as a result, all competing formats die of market starvation.

If Atmos can recreate in headphones something equivalent to or better than the binaural recording mentioned in this instalment, but with all the benefits of multitrack audio production, it will be amazing and I’ll be lining up for it. In the meantime, stereo has been with us since the 1950s and has outlived every competitor.

The only legacy I can think of from the preceding surround/immersive formats that remains a significant and influential part of today’s popular music production is SSL’s Quad compressor. It was part of a late 1970s future-proofing gamble in anticipation of a four-channel surround format becoming successful – which is why SSL’s 4000 series consoles had front and back stereo buses (relatively simple to achieve) but no joystick on every channel for panning between them (super expensive, fiddly and unjustifiable). The Quad compressor, and its imitations/derivatives, has become an essential part of popular music production. We mostly use it in stereo, of course, reinforcing my belief that anything in the surround/immersive space that doesn’t work in stereo ends up floating for eternity in the surround/immersive outer space.

I am glad you’re enjoying it Chris!

A very interesting perspective. In mixing and mastering, I find that using headphones (Neumann NDH 20’s and NDH 30’s) are quite useful when used in conjunction with very-nearfiled monitors (Neumann KH 150’s and KH 120 II’s). It is remarkable how similar they sound.

I agree about the similarities between Neumann’s headphones and monitor speakers. I have discussed how that kind of translation is achieved in the second and third instalments. I suspect that Neumann have created their own equivalent to the Harman Target curve, based on using their own monitors. Not many headphone manufacturers can do that because they don’t make monitor speakers as well. It’s very interesting when a company manufactures both and can use one as a reference for the other; the whole goal of a target curve suddenly becomes useful in the production stage rather than just a matter of listening preferences for consumers.