On The Bench: Where’s The Spares

Repairing new equipment is getting harder and harder, even for the techs. This issue, Rob Squire asks: ‘where have all the service manuals and spare parts gone?’

Text: Rob Squire

Through good fortune, timing and the weight of experience I get to see a wide range of audio widgets passing across my tech bench: older gear in need of simple repair, other gear requiring much greater attention – a re-birthing of sorts – and relatively new gear that’s often still under warranty. This last couple of months has been a particularly busy time, so this issue I thought I’d share with you some stories hot off the soldering iron.

DISTRESS SIGNALS

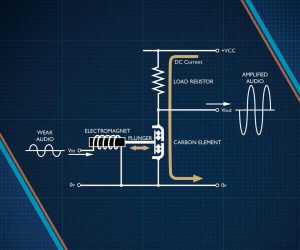

I received a flurry of emails in June from the owner of an ELI Distressor that had gone haywire, and also from the designer and owner of Empirical Labs, Dave Derr, asking if I could sort it out. I’ve been under the bonnet of a couple of these units over the years, and despite ELI’s practice of removing all identifying marks from components and not releasing any technical documents, I was happy to take on the job. Normally under these circumstances a job like this can be a nightmare. If you’re lucky and have your mojo working, the repair can be successful, however, it’s hard going into it feeling confident with these twin obstacles of no schematics and anonymous parts blocking the path. This is the sort of situation that causes most technicians to groan in despair and wonder what the world has come to. When you’ve been around long enough to remember when Tascam provided a full service manual at the back of each and every one of its operator manuals you know things have changed. Indeed, there was a time when no self-respecting, self-reliant studio or radio station would consider the purchase of any equipment unless a full service manual was supplied. Moreover, product sales were almost always contingent on technical support, manuals and locally stocked spare parts.

The upside with ELI products – in the absence of any comprehensive service manuals – is the rapid, clear and enthusiastic technical support that comes straight into my inbox direct from the designer; something that’s almost as rare as locally stocked spare parts in today’s world.

CLIENT SATISFACTION

With the lid off the Distressor – which was incidentally insisting on applying 30dB of compression regardless of the operator’s intent, and regardless of whether there was even a signal present to begin with – I was able to shoot Dave a couple of questions about expected voltages and chip numbers. The next morning there was an email response answering every one of my questions in detail, and not long after I’d turned the soldering iron on, the unit was repaired. I shot off a reply to Dave saying all was well, to which he requested that I run the unit for the whole day as a final confirmation of the repair, and to ensure that nothing else cropped up. He also requested an invoice for the repair, including shipping the unit back across the country to its owner. Now, here’s the sting… this unit was secondhand and a number of years out of warranty, yet the manufacturer is asking to pick up the tab for its repair! My correspondence with Dave about this job concluded with immediate payment of my invoice and a sincerely expressed thankyou to me for looking after his client. Wow, a manufacturer who considers the purchaser of a secondhand product several years old their client! Is Dave crazy or does he know something that no-one else seems to?

Something I’d like to make clear here is that this is not the first time I’ve had such a pleasurable experience dealing with ELI, so it’s no aberration. What makes this incident so remarkable is that it stands in stark contrast to the broad experience that service technicians face day in and day out obtaining clear and efficient support from manufacturers and distributors.

THE RESPONSE CURVE

The flipside of this story are two recent cases where enquiries about the price and availability of replacement parts disappeared down an apathetic plughole. One enquiry kicked off with a couple of polite emails to the local distributor to prompt a reply about a single part. These were eventually responded to with a request for the serial number of the unit. A couple of emails and a phone call later… nothing. Another month and a half of silence went by before I was finally contacted by the frustrated owner to see if I could make any further progress with it. Rather than beat my head against the same wall, I picked up the phone and called the support line for the USA-based manufacturer, who was happy to sell me the part I needed over the phone just by quoting my credit card. This experience was repeated again with a different product and distributor, where, despite emails and phone calls, the distributor never even responded to say that they either had or didn’t have the unique part I required to repair the unit, or that they would even sell it to me if they did. In this case I tracked down the previous distributor of the product line who happened to have the spare part I needed languishing on the shelf, and were pleased to offload it. All this detective work and arm-twisting is tiresome and ultimately adds to repair costs. Indeed, in both these cases I spent more time obtaining a part than it took to diagnose the original fault and install the new replacement… when I could finally get one!

SUPPORT – THE DEAL MAKER

There has been a lot of grizzling of late about the increase in folks purchasing products overseas, exasperated by the high Australian Dollar and the weakness of the US economy; all of it ultimately leading to ‘the downfall of local distributors and retailers’ they say. As a technician, let alone a customer, there’s no doubt about it; I need the local guys, but by the same token it seems to make sense to me that one thing they clearly have to offer that lifts them above the world wide pond of online stores, is local technical support. I also reckon that many distributors, with the help of the manufacturers they represent, could really lift their game in this department. Hell, if they really pushed the envelope it could be a deal-making promotional tool.

Then, of course, there’s the gear that’s old; so old that the original manufacturer doesn’t even exist anymore, or if it does, there’s no-one at the company who’s ever seen the product. There may not even be a faded copy of the original service manual on the company’s shelves, let alone spare parts. This scenario might seem strange, but it happens all the time. A case in point recently involved SSL in England where, after banging my head against the armrest in frustration at the litany of faults in a particular SSL 5000 console, I picked up the phone and called the home of SSL and asked if I could please talk to their most experienced console engineer. I felt a shudder down the phone line when I mentioned the words “5000 series” to the man at the other end of the line, and my own shudder upon hearing his carefully worded response: “we don’t have any documentation and we don’t have any spare parts.” When I persisted in asking a few technical questions about its operation I was met with a second, more unnerving insight: “it sounds to me like you know more about that model than anyone now working here.” This wasn’t the support I was hoping for, but still, the model is now 25 years old and taking this situation in my stride was what I’m paid to do.

I felt a shudder down the phone line when I mentioned the words ‘5000 series’ to the man at the other end of the line, and my own shudder upon hearing his carefully worded response: ‘we don’t have any documentation and we don’t have any spare parts’

CAPPING THE COSTS

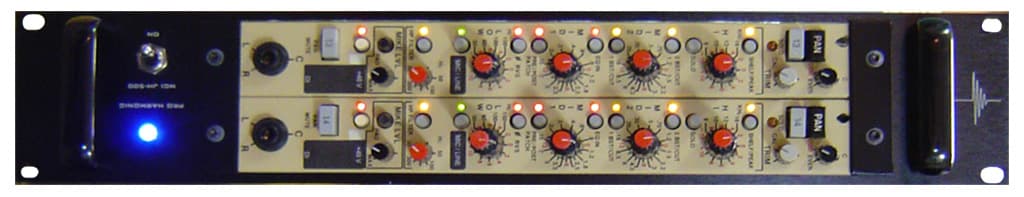

I’ve had a number of old large consoles passed my way lately and I’m beginning to notice an interesting relationship between their secondhand purchase price and the expectations of the new owners about the costs involved in getting them installed and working properly – namely, that there isn’t one. It has never been cheap to install and maintain a large format mixing console and it certainly doesn’t get cheaper as they get older and more worn out. The harsh reality of this situation is borne out by the numbers of consoles being ratted out for parts, with input channel strips landing here on an almost daily basis to be racked up into standalone units. The cost of refurbishing a pair of channel strips, modifying them to work outside the console, putting them into a case with a power supply and connectors isn’t cheap but its digestible, and bang-for-buck can be a good proposition. Conversely, the cost of getting a neglected 30-year console up and running, installed and wired into the system can easily cost more than its secondhand price. Yet rarely do I see anyone budget for these costs or even research the condition of the console and its ability to be repaired, let alone the cost to do it. I talked specifically about capacitors in the last issue of AT and these are likely candidates for failure in a console, and just the replacement costs in this job alone are often comparable to the value of the console. And let’s not mention switches and potentiometers that inevitably become scratchy and intermittent – not the sort of thing you need sitting across your mix. These are often unique to the manufacturer and sometimes difficult (or impossible) to source.

Despite not running a studio and it being quite a few years since anyone paid me to pull a mix, I still get excited by audio equipment – old and new – so I understand how the heat of the moment can cloud sensible enquiry when the acquisition of a new widget arises. However, standing back and putting the smart hat on, it’s always worth running a few questions up the flagpole. For a new product, what do I stand to gain or lose by not buying it locally, and is part of this gain likely to be worthwhile after-sales support? Put the sales guy on the spot, or better still, pick up the phone and call the local distributor and ask about availability of spare parts, and where their authorised repairers are located. Get at least some sense of how well this new product will be supported. If you decide to send your dollars overseas be really clear from the outset that, by the book, for warranty support you’ll need to return the item overseas at your cost, and down the track when the warranty expires, there’s no guarantee the local distributors will provide replacement parts even though you’re paying them for the repair. Oh, and please, if you’re purchasing equipment from the USA, switch the unit over to 230VAC mains before you plug it into the wall and blow your shiny new purchase out the door. If you aren’t totally confident that your unit is set to 230VAC mains power, spend a few dollars and take it to a tech to check this out for you. There are mountains of dead USA purchases piling up in workshops around Australia resulting from goods set to 115VAC landing here and being plugged in willy-nilly by impetuous owners.

If your new purchase is old school, whether it’s a 52-channel console or a 1960s condenser microphone, if it costs anything more than weekend flash money, get a technical report on the unit. This will at least give you a feel for the real cost of bringing the device up to speed so that it does its job and benefits your setup, rather than misbehaves to the point of distraction.

PS: ON THE BENCH, LIVE!

I’ll be dragging a good slab of my workshop up to AT World at Integrate this year. The soldering iron will be on and I’ll be up to my elbows inside something interesting. Drop by and say hello while you’re there and feel free to quiz me on the state of your audio equipment. On Wednesday 31st at 12.30pm there will also be the ‘Tech Forum’ where I will join a bunch of techs much smarter than to chat about electrons, music and how to get the two playing happily together. Until then…

RESPONSES