View From The Bench: DE-esser

How de-essers tame those frisky fricatives and slippery sibilants.

I once had the pleasure of downing some beer and peanuts with a crusty old recording engineer — let’s call him ‘Fred’ — who in the 1980s was employed by one of the top studios in Melbourne. Fred used to work with advertising customers, creating soundtracks for television and radio commercials, and he told me the following story…

In jeans and a t-shirt, pony-tailed Fred was in the control room doing mix passes and balancing the main character’s voice in an advertisement. Sitting next to him — sporting a suit, tie and cuff-links — was a clipboard-wielding executive from the ad agency. The two weren’t exactly candidates for a bromance. The ad guy figured Fred for an insect-harbouring, scruffy hippie, and Fred thought the ad guy was a craven weasel who would sell his own grandmother to turn a profit. So Fred gets the mix just about right and asks, “How’s that?” The ad guy responds, “Sounds a bit ‘essy’!”

Now, at that particular moment in history the physical number of de-essers in Australia was precisely zero. Fred’s thinking was that the ad guy had picked up an industry magazine and read about some American engineer using one, and was simply seizing the opportunity to be a smart arse. “Do you have a de-esser?” He queries. After a pause, Fred says, “Yes, we do, but it’s in use elsewhere. How about I bring it in tomorrow and we’ll finish off?” Ok…

That night Fred goes home, grabs a two-unit rack spacer panel from a box in his garage, and about an hour later it has been adorned as follows: On the left there were two jacks marked IN and OUT, simply hard-wired together. In the middle sat a VU meter, with a potentiometer to its right. Unseen on the rear, a battery was wired to the meter via the potentiometer so that rotating the pot would cause a convincing deflection of the needle. Everything was marked with rub-on lettering, which looks like proper printing if you don’t get too close. As a finishing touch, Fred put the words De-Esser and a made-up brand name in the corner, followed by the letters USA. He told me in those days if gear was from America, you’d think it must be good. The next day he took his new contraption to the studio and screwed it into the rack.

Enter the ad guy, who seems impressed. Fred gets the mix up, and inserts the ‘De-Esser USA’ which effectively functions as a cable joiner. He rolls tape. “Too essy”, says the ad guy. Fred winds the knob clockwise, and the needle moves a bit. “How about that?” “No, still a bit essy.” The knob is rotated more. “How about that?” “Just a bit more…” The needle moves further. “Perfect”, says the ad guy.

Result: One happy customer who goes forth to boast how the studio where he gets his commercials recorded has a De-Esser! Later, Fred starts to get phone calls from engineers at other studios who are somewhat suspicious…

What interests me most about Fred’s anecdote is the underlying insinuation that de-essers themselves engender a kind of technical fraud, because even if you use one your listeners won’t be able to tell the difference. Indeed, while he was telling me his story, I recalled how I reacted as a youngster, hearing about them for the first time, and asking what they did. Nobody I knew had a proper idea. We were all very confused.

So what is a de-esser, and where did it come from? What does it do, and how does it work? Is it an essential tool of the studio, or does it just remove pixie dust from your recording, and replace it with bullshit?

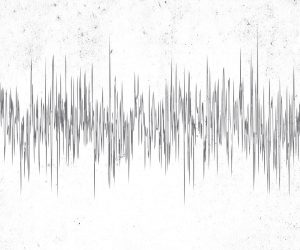

SIX SILVER SWANS SIBILANTLY SQUAWKED

I suspect most readers of this article already own a digital recording program with a de-esser plug-in included, and may have had a bit of a fiddle. Those readers will have seen that the plug-in enables them to apply instantaneous gain reduction to sibilance and fricatives, which are the whistly and spitty bits of human speech. They often appear in our recordings with un-natural prominence above the average power of supporting dialogue, and can be as annoying as a finger that emerges from the loudspeaker to PoKe you in the TemPle wiTH eFFry SSSSSyllable.

‘Fricative’ is a jazzy word, which would be better suited to describe a style of dancing or cooking. Instead, it refers to sounds which emerge from our mouths that use friction as a substantive part of their mechanism, rather than just tonal resonance. The letter ‘T’ is a good example, as it involves blocking the airflow with your tongue, and then suddenly releasing it. Fricatives that don’t entirely block airflow, but which involve the friction of air through a narrow gap or across the teeth, tend to have a hissy nature, and are referred to as ‘sibilant’. The letter ‘S’ is the poster boy for sibilance, and it is from him we get the term ‘essy’ and the generic name for any device designed to reduce the amplitude of such fricatives when we don’t like them.

These noises all contain the bulk of their spectral energy in the 4-10kHz band of frequencies, while the main body of non-fricative speech resides four or five octaves lower, in the 100-500Hz band. Fricatives are a natural part of speech, but they can present challenges — and management or intervention is sometimes required.

TESST ONE TSSOOO

Some fricatives contain plosive sounds which from the point of view of a microphone can look like a shock-wave. Earlier I described the letter ‘T’ as being produced by a sudden un-blocking of the airway by your tongue. This produces not only the high ‘t’ sound, but also a sudden pressure wave of somewhat greater energy, and it can hit the mic element with a tiny thump. It’s as forceful as a bullant knocking on your front door, but when added to the intelligible part of the sound, the resultant recorded ‘T’ may exhibit more emphasis than initially heard by the naked ear.

Once that sound enters the recording equipment, it faces additional challenges. It is not uncommon for a vocal track to receive an equalisation boost in the top end, to improve intelligibility and enhance natural harmonics which may be pleasing to the ear. However, since fricatives reside in the same range, they will also be boosted, increasing their elevation above the average level of non-fricative content.

Furthermore, it’s quite common to compress a vocal track, to make it sound more powerful and consistent. Compressor attack times favoured for vocal performances are generally too slow to grab leading edges, with gain reduction applied only to the main body of the sound, making the fricative louder still.

Turning down the treble is an obvious way to reduce fricatives in a recording, but the audio track is also dulled as a consequence, which may be undesirable. We really want to be able to remove them while leaving the surrounding audio intact.

DE-OLDEN DAYS

As we saw in the article about compressors (Issue 123), Hollywood was taking control of audio dynamics from the very first days of the ‘talkies’ and de-essing appeared about 10 years later. In 1939, Warner Brothers Films developed a system for reducing excessive sibilant energy in speech as full modulation was approached on the optically-recorded film stock. This was probably the first time the idea had been put to industrial use, and control of sibilance in films has been ongoing ever since.

The same idea eventually crossed over into the record industry, in the area of disc cutting and mastering. If a high frequency signal has too much amplitude, it can be difficult for a playback needle to physically track the groove at speed, so it made sense to place an upper limit on such undulations. One example from the early 1960s was a record cutting lathe manufactured by Danish company Ortofon, which included its STL631 Treble Limiter as part of the valve-amplified cutter control circuit. With a patch, it was possible to use the 631 as a stand-alone unit, and some are still in use today — not just in vinyl mastering, but also recording.

The earliest reference I can find to a proprietary stand-alone unit is the Orban 516EC Dynamic Sibilance Controller made in San Francisco in the mid-1970s. It was a FET model designed, says Orban, for “the recording and motion picture industries.”

Prior to the wide availability of purpose-built units, sibilance reduction was usually achieved by employing a compressor with a high pass filter inserted in its side-chain. David Nicholas (INXS, Pulp) says that way back at the dawn of time he used, “something or other by Valley People, probably a Dynamite from the ’70s configured to work as a de-esser, and it was all a bit troublesome and complicated to set up. But when the classic dbx 902 came out in the ’80s, that was it, and every rack in the world had a pair of them.”

I asked him about the early reputation of de-essers, as a box that didn’t really do much. His response was quick, and to the contrary. “One of my worst nightmares was too much de-esser during the tracking of Midnight Oil’s Blue Sky Mining, making the word ‘save’ sound a bit like ‘shave’. It was tape, so we couldn’t doctor it like you can with digital. The fans picked up on it and used to sing along at the gigs… “who’s gonna shave me!” It became a hit, but I lost a great deal of sleep over it. Since then I have never used a de-esser during tracking; only on the back end. With a de-esser, if you can hear it working, then it’s too much.”

One of my worst nightmares was too much de-esser during the tracking of Midnight Oil’s Blue Sky Mining, making the word ‘save’ sound a bit like ‘shave

FACTORY FAB’D FRICATIVE FIXERS

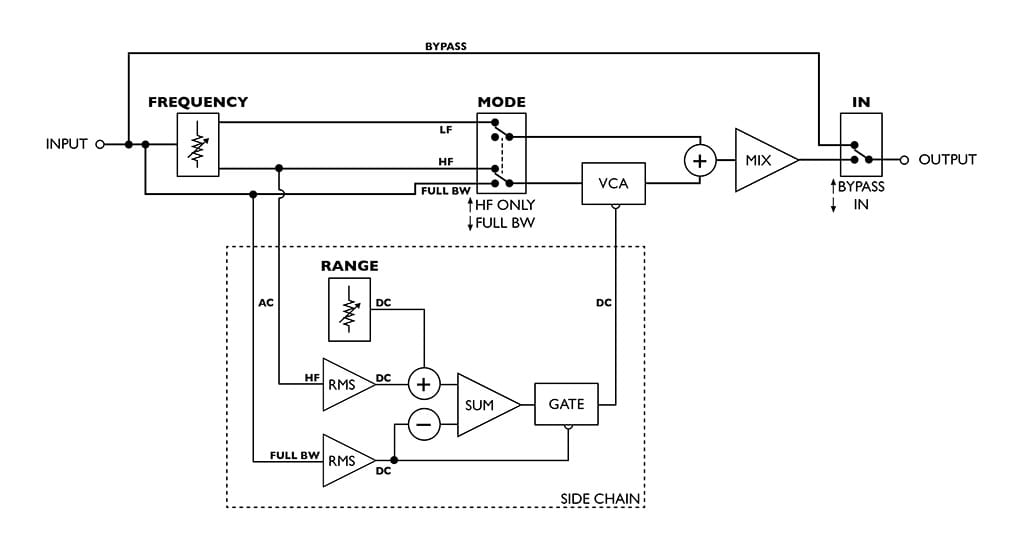

Simplified, a de-esser is a compressor in which the control circuitry is triggered by excessive amplitude within the fricative range of frequencies. As in the example above, a normal compressor can be used if the audio path to the gain reduction element is interrupted by a high pass or band pass filter, causing the compressor to attenuate only when the signal amplitude crosses a threshold within that band. If the attack and release times are set to react quickly, short fricative transients can be reduced substantially without affecting the audio that precedes or follows. Typical attack times are usually a millisecond or less, with release times varying between two and 50ms. In a proprietary de-esser these times are fixed, depending on what the designer finds pleasing to the ear.

These days, a device like the makeshift one above is usually described as a ‘high frequency limiter’ and a reasonable quality de-esser is likely to include additional refinements. Principal among these is ‘dynamic threshold’ where fricative energy is compared with overall energy, so that gain reduction only happens when high frequencies exceed some given ratio against the full bandwidth signal. If a singer crooning a verse suddenly belts out a much louder chorus, the increase in general volume would put more signal across the threshold of a high frequency limiter, and result in more de-essing. However, since louder singing causes negligible change in the ratio of high to low vocal frequencies, a dynamic threshold promises to keep the amount of de-essing more or less consistent.

In 1980, dynamic threshold was a big feature of the dbx 902, and worked so well that it was assumed to be a dbx invention. But other manufacturers had already employed versions of it, including the Orban 516 of the previous decade. The real achievement of the 902 was to get the ratio comparison bits working over a 64dB range — wider than any likely musical performance — so the unit could almost be treated as ‘set and forget’ within the signal chain. In the 1980s such functionality was welcomed, since it was still common practice to record a whole band at once, and a sound engineer had plenty of other places to look during a take.

The dbx 902 uses a voltage controlled amplifier, or VCA, as its gain reduction element. A VCA is an amplifier in which gain is kept proportional to an external voltage applied to its control terminal. Valley People boasted a proprietary VCA in its Dynamite compressors of the late ’70s, but again it seems dbx was the one to perfect this technology, which it also used in the legendary dbx 160 compressor. These days if you want to buy a VCA to solder into your gadget, you would look no further than those made by THAT Corporation, a company founded by guys who used to work at dbx.

The 902 uses a 12dB/octave active crossover circuit to divide the audio signal into high, low, and full bandwidth signals, which are dealt with separately (see diagram). Today the dbx 902 is superseded by the 520, made to the same recipe but with updated components.

The 902 set a benchmark, but other manufacturers remind us there are different ways to do it.

The BSS DPR-402 dynamics controller incorporates two separate side-chains — one for compression and one for de-essing — which simultaneously dictate gain reduction to a

single VCA.

Empirical Labs makes a number of VCA de-essers. The Lil FrEQ includes de-essing as one function within a tone equaliser unit, and allows operators to switch between dynamic threshold de-essing, or high frequency limiting, as desired. The DerrEsser includes a ‘listen’ button that allows you to preview the audio content being removed.

The Avalon VT-747SP is an optical compressor which allows independent threshold control for high and low frequencies, so it can be set up as a high frequency limiter.

My own Prodigal de-esser uses a FET as the control element, with dynamic threshold created by adding the averaged full bandwidth signal to a user threshold setting — the ‘ESS’ knob. Turning clockwise, the result is more essy, and anti-clockwise, less essy.

DE-ESSING UP FOR FAMILY OCCASIONS

De-essing is not limited to the reproduction of the human voice, but is also useful for other sounds containing high frequency fricatives, such as a plectrum as it thrashes across acoustic guitar strings, or to remove hi-hat bleed from a snare drum mic.

I recently recorded Mrs Tech Bench, who is a great lover of Himalayan music. She plucked through a few hot takes on her dramyin using a traditional bone plectrum, which can sound a bit peaky, especially if you are using a condenser mic. My solution was to slap a de-esser across it, which worked a treat. Playing it back, I was impressed at how the subtle reduction in pick noise gave way to the warm, full-bodied sound of the instrument. “How’s that?” I asked. “It sounds the same as before,” she said.

Perhaps Fred was an ’essing genius after all.

RESPONSES